Does A Rich Entrepreneur Or An Inmate In A State Prison Have Access To Services That Others Lack?

State Prisons and the Delivery of Hospital Care

How states set up and finance off-site care for incarcerated individuals

Overview

Delivering acceptable medical intendance to the more than 1 million adults in state prisons is a growing challenge for states, in part because of the high costs and complex logistics required to hospitalize people who are incarcerated.

While nigh care for incarcerated individuals is delivered on-site, some of them periodically need to be hospitalized for acute or specialized care. As is true generally, this treatment is expensive because of the labor-intensive and sophisticated services provided. And hospitalizing someone who is in prison brings added expenses, such every bit providing secure transportation to and from the infirmary and guarding the patient round-the-clock. Country officials nationwide are under increasing pressure to comprise hospitalization costs while likewise ensuring the constitutional right to "reasonably acceptable" care.

Hospitalization expenses are already a pregnant portion of correctional health intendance spending and are likely to grow if prison trends go on. The average historic period of those behind bars is ascension, and the health needs of these individuals—like older people outside of prison—are more all-encompassing than those of younger cohorts, including more hospitalizations. Country officials are also noting an increase in the amount of care required for all adults inbound correctional facilities. Looming over these considerations is the future management of national wellness intendance policy, peculiarly the function of Medicaid, the federal-land program for low-income individuals.

With these challenges in mind, The Pew Charitable Trusts explored hospital treat people incarcerated in state prisons, tapping data from two nationwide surveys conducted past Pew and the Vera Institute of Justice and from interviews with more than 75 state officials. This first-of-its-kind analysis of hospital intendance for this patient population is part of a broader examination by Pew of correctional health care in the United states of america.

This report volition discuss the means states arrange and pay for hospital care for their incarcerated population and how such care supplements on-site prison wellness services. Its findings include:

- Off-site intendance costs are a significant role of correctional health budgets. For case, Virginia spent 27 percent of its prison health intendance budget on off-site infirmary care in 2015, while New York spent 23 percent.

- The wellness care delivery model that state prisons use to provide on-site services informs decisions they must make regarding hospitalization arrangements, including who holds authority to send someone off-site, how the care is coordinated and reviewed, and which entity pays the beak.

- The federal Affordable Care Act (ACA) offers country policymakers who elect to expand their Medicaid programs' eligibility a way to reduce inpatient hospital spending.

- Though incarcerated individuals always volition need to exist treated at hospitals for sure conditions or tests, some states take promising practices to avert some off-site care, saving money and mitigating public safety risks.

The report'southward word of land approaches to providing care to incarcerated individuals is designed to help the officials involved in setting hospitalization policy—lawmakers, prison and hospital medical staff and administrators, correctional officers, and sometimes private contractors—improve manage costs while working toward or maintaining a high-performing prison wellness intendance system.

States look to hospitals to provide range of services

States have a ramble mandate to provide people in prisons with necessary health care. Prisons typically provide on-site primary care and basic outpatient services. Departments of corrections besides usually adjust for some prisons within their system to house specialized clinics or units.1 Such facilities are designed for people with acute or chronic illnesses that do not crave highly specialized off-site services; tin provide recurring care, such every bit kidney dialysis; or can house patients recuperating after a hospital stay. Still, every correctional organization'south on-site facilities and equipment are express, so all states rely on hospitals for some specialist consultations, diagnostic tests, surgery, and other services.2

Types of Health Care Outside Prisons

- Off-site care:Any care provided off the prison's premises. It could be provided at a hospital, surgical center, or specialty clinic, such as for radiology or dialysis services.

- Inpatient hospitalization: An admission to a medical institution, such every bit a hospital, for longer than 24 hours. This is the just type of treat which country Medicaid agencies may provide coverage for incarcerated individuals, if they are eligible and enrolled in the program.

- Outpatient intendance:Emergency, diagnostic, or therapeutic services that exercise not require the patient to exist admitted to a infirmary.

Off-site care represents a sizable portion of corrections departments' health expenditures. Hospital intendance accounted for nearly 20 percent of health spending in 10 states between 2007 and 2011, according to Pew research. More contempo data from two boosted states, New York (23 per centum) and Virginia (27 percent), showed the proportion may now be greater.3

While the ACA lowered inpatient hospital expenses for corrections departments in states that expanded their Medicaid programs, off-site care remains a fiscal claiming, especially when considering ancillary transportation and security costs. (A discussion of how some states' infirmary payment policies have changed due to the ACA'southward optional expansion of Medicaid eligibility tin can exist found in the "Medicaid expansion has helped cut costs" section.)

Older individuals take more need for specialized intendance because of a greater prevalence of chronic conditions such as heart disease, cancer, and diabetes.4 In the community, older people take significantly higher rates of hospitalization and brand more emergency room visits than do others, raising health care costs for this sector.v Prison populations are also aging, with similar implications for spending. From fiscal twelvemonth 2010 to 2015, the share of incarcerated people 55 and older increased by a median of 41 percent in the 44 states that reported this statistic, indicating that corrections departments face rising health intendance costs for the foreseeable future.6 Moreover, most incarcerated individuals experience the effects of age sooner than people exterior prison considering of such bug as substance use disorder, often inadequate preventive and chief intendance before incarceration, and stress linked to isolation and the sometimes violent environment in prison house.

Virginia'southward corrections section illustrates these patterns. The cost of off-site care for incarcerated adults 55 and older is almost double that for younger individuals. While 12.2 percentage of the state's prison population was in the 55-plus historic period bracket in financial 2016, they fabricated up 28 pct of those receiving off-site care that year. Their treatment deemed for 40 percentage of the department'due south hospital nib.7 States that have an even higher proportion of aging inmates than Virginia probably spend a larger proportion of their corrections department health dollars on off-site services.

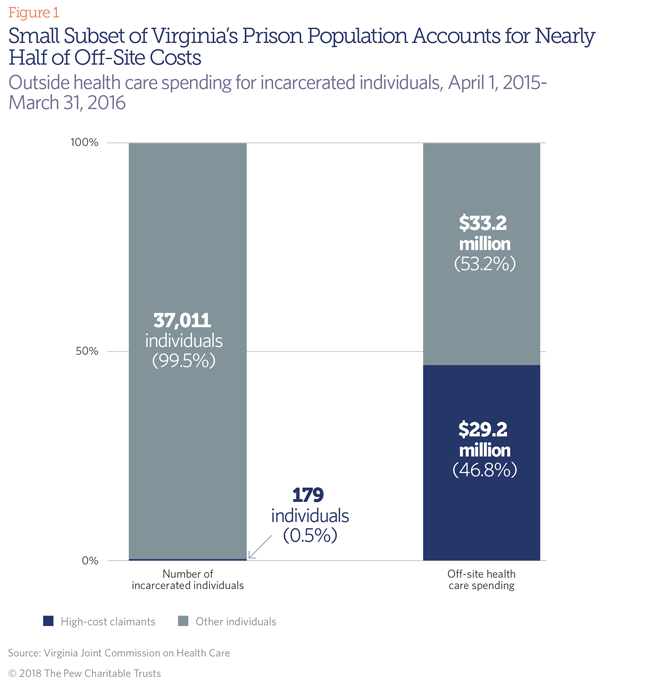

In add-on to those who are aging, a relatively small subset—disproportionately but non exclusively older than 55—is a particular cost challenge. (Meet Figure 1.) They nearly commonly have cancer, heart disease, and other severe conditions. Nigh one-half of the $62 million that Virginia spent on off-site wellness intendance in fiscal 2016 was for 179 people, who made up less than 1 percent of the state's prison house population.viii

Models states employ to structure prison hospital care

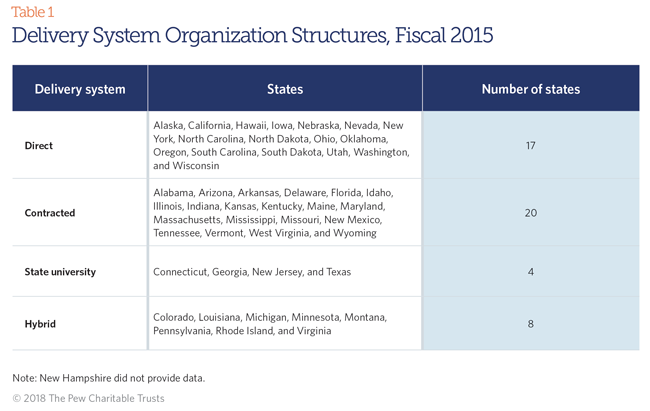

Creating a prison health system starts with designing on-site access to primary intendance and mutual outpatient services. Off-site services supplement such care. (See Table 1.) Pew and Vera's enquiry revealed that state corrections departments evangelize on-site care using one of 4 systems:

- Directly model. State-employed corrections department clinicians provide all or well-nigh on-site care.

- Contracted model. Clinicians employed past one or more private companies deliver all or most on-site intendance.

- State university model. The country's public medical school or affiliated organization is responsible for all or almost on-site intendance.

- Hybrid model. On-site intendance is delivered by some combination of the other models.

States select a model based on historical patterns, staffing needs, policy preferences such as privatization, and other factors. The model officials choose is significant in function because of the bear on it has on hospitalization arrangements. For example, in the contracted-provision model, state officials must comprise rules into a vendor's contract that delineate who has potency to ship someone for nonemergency hospital care. Those rules cover such questions as, Can the contractor'southward medical employees determine on their ain to transport a person to a hospital or do they need approving from a land official, such as the corrections department's medical manager? The agreement must too analyze whether the contractor, the corrections department, the state Medicaid bureau, or a combination of the three pays the off-site care neb.

Which model is followed also affects the way payments are tied to care. Most corrections departments that outsource their on-site intendance negotiate a contract with their health vendor that establishes a capitation—a fixed per-person, per-month payment—that vendors receive for caring for the individuals in the prison organization.9 Corrections departments counterbalance how all-time to obtain good-quality care at a reasonable cost while balancing the contractor's financial obligations.

The contract between the corrections department and the vendor must detail what services the capitation covers. Considering of the potential to incur substantial and unpredictable expenses, vendors can be apprehensive about bold financial responsibility for patient hospitalizations. Thus, some states hold to exclude completely (carve out) or partially (risk share) such expenses from the vendor's contract, retaining that responsibility fully or in part. Such arrangements may apply only to off-site outpatient care and any inpatient care not eligible for coverage by other payers such as Medicaid. States that expanded their Medicaid eligibility under the ACA might as well cull to cleave inpatient care out of their vendors' contracts since so many hospital stays will qualify for coverage under that police force.

Arkansas, Illinois, Pennsylvania, Vermont, and Virginia fully or largely contract out their on-site prison health care but carve out inpatient hospitalization costs. At the other extreme, Arizona, Delaware, Florida, Indiana, Kansas, Kentucky, Massachusetts, and Missouri hold vendors completely responsible for such care through an all-inclusive capitation rate. States that use the risk-share model include Maryland, Michigan, Minnesota, Tennessee, West Virginia, and Wyoming, but their arrangements vary.

The 17 states that deliver on-site prison health care directly and the four that use a state university model pay for the cost of off-site care in varying ways. For instance, lawmakers in Connecticut and Iowa advisable funds to embrace the price of inmate patient medical services at the University of Connecticut hospital (the state correction section's primary hospital partner) and the University of Iowa Hospitals and Clinics, respectively. But when Iowa's corrections department uses a community hospital, it pays for the care out of its own budget.ten Hospitals bill the New York state Medicaid agency for inpatient care of Medicaid-enrolled individuals but charge the corrections section for outpatient care and the inpatient care of offenders who are not enrolled in Medicaid.11

Custody Arrangements

Almost 9 in 10 individuals nether the legal authority of state departments of correction in fiscal 2015 were housed in land-run prisons. The operation of these facilities, including health care, is directly managed by state officials and carried out by a mix of state employees and individual vendors.

A bulk of states also put some of their incarcerated population under the physical custody of privately owned and operated institutions or local jails. Private prisons are for-profit entities that manage all correctional functions. Jails primarily contain people pending trial and those convicted of misdemeanors who are serving sentences of less than ane yr.

State decisions most when and how best to make use of these alternative settings result from a number of considerations, including cost and space. States retain legal liability for health care provided to those under their jurisdiction, even when the services are provided outside state-run facilities. States lose some directly control and influence over the care that is provided—though they can seek to rails performance against established quality requirements—and typically take less admission to detailed cost and spending data, as wellness care costs are incorporated into correctional per diem payment totals.

How officials approve and review hospitalizations

Nonemergency hospital care requires authorization in advance by a corrections department to ensure in that location is not an advisable, less expensive treatment available. In this way, officials effort to control costs while complying with required standards of care. All states take a organization to ensure example review for such authority, regardless of whether the state or a private contractor manages on-site health intendance. Most states qualify the contractor's medical director and/or the medical director of the state corrections agency to consider requests from the prison medical staff for preapproval for such nonemergency treatments as a hip replacement or hernia repair.12 The director may approve the proposed procedure, refuse it, or suggest an alternative handling. 13

Hawaii, a direct-provision land, is a good instance of how such reviews are conducted for the portion of its prison house population housed in the state. The section of corrections' medical manager heads a console of country physicians and nurse practitioners who review requests from prison medical providers to send a person to a infirmary or specialist outside the prison. The console makes a decision based on clinical findings and other criteria, such equally customs standards of practice for the service and the person'south remaining time in prison house. If the request is approved, the corrections security staff is told to arrange screening, transportation, and supervision during the off-site stay. After the handling, the off-site hospital and specialist must inform the committee of their diagnosis, exam results, treatment provided (including medications), and hereafter recommendations.fourteen

Other states generally exercise much the aforementioned for nonemergency care. In Connecticut, physicians from the University of Connecticut and the correction section conduct the review, in part considering the university—which is providing on-site health care until mid-2018—also operates a 10-bed inmate unit of measurement at the university hospital. The country requires the university to report the number of requests for off-site care and the percentages of those that are approved and denied, and for what reasons.15

Hospitals must also preapprove inpatient hospitalizations that corrections departments wait their state Medicaid agency to comprehend to ensure that the admission meets Medicaid guidelines.

Country corrections officials tin can also review hospitalizations retrospectively. As in nonprison settings, a rise in "preventable hospitalizations"—admissions due to conditions that are mostly treatable in a primary care setting—could signal that a vendor or its staff at a facility is not providing timely, effective chief care or using prescription drugs effectively. Pennsylvania corrections officials, for case, scrutinize each incarcerated individual's treatment that preceded hospitalization to larn if it could have been averted.

Another area of review involves infirmary readmissions. Repeat trips to the hospital following initial treatment increase costs and may betoken inadequate care in the infirmary or during the patient'due south recuperation. In 2012, the federal government fabricated readmissions a focal betoken for improving care after finding that nearly 1 in five Medicare patients returned to a hospital within 30 days of discharge.

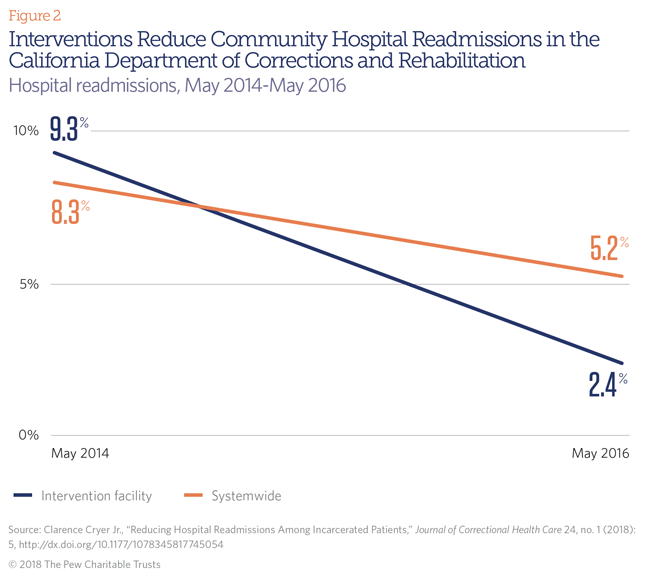

Attempting to reduce avoidable readmissions, California officials chose to focus on the country prison with the highest charge per unit. (Run across Figure 2.) They developed an algorithm to identify patients most at risk for readmission 16 then required a registered nurse to check on them within one business day after they returned from the hospital. Doing so meant that incarcerated individuals who had had surgery, for example—and might be decumbent to an infection—would be treated at the first sign of 1, reducing the likelihood of rehospitalization. Over two years, the infirmary readmission rate for this prison dropped from 9.3 to two.4 percent.17

Corrections departments can contract with independent third parties to review hospitalizations, every bit Ohio, Nevada, and Virginia do, but such reviewers and hospital and corrections officials demand to consider incarcerated individuals' special circumstances when applying standards to admissions and lengths of stay. For example, a infirmary should not exist penalized for a longer-than-average stay if it stems from a lack of available correctional staff to transport the patient back to prison house. Or a person might need to remain in the infirmary longer than a general patient would if the prison to which he volition return lacks proper recuperative services, such as would ordinarily exist provided by a visiting nurse or a community rehabilitation facility.18

Deciding When to Hospitalize

Requests for hospitalization generally fall into three categories, depending on the urgency of the handling. Florida, for example, defines the categories every bit follows:

- Emergencies: Life- or office-threatening conditions that require immediate handling, such equally a center attack. In these situations, the formal asking procedure is non used. A 911 responder tin decide to have the incarcerated individual to the infirmary, collaborating with a medical official or, if i is not bachelor, deciding on their ain to accept the patient to a hospital.

- Urgent: Conditions that must exist treated inside 21 days to avoid condign emergencies.

- Routine: Weather that tin tolerate a handling delay of 45 days. For nonurgent diagnostic tests or surgery, such equally a hip replacement, some states allow even more fourth dimension to make up one's mind whether a procedure is needed and, if so, whether it must be performed earlier the end of the person's sentence.19

State strategies vary in locating hospitals

Regardless of the on-site health intendance delivery model, corrections departments need to identify hospitals capable of providing supplemental services and willing to care for incarcerated individuals. Their efforts are complicated by the fact that correctional institutions are scattered throughout a state, ofttimes in rural areas, and vary in size, security level, and the age and gender makeup of the incarcerated population. They besides differ in their on-site capabilities.

Hospitals, likewise, are dispersed throughout a state and have varying capabilities that do not necessarily mesh with the needs of those incarcerated nearby. States often place their oldest, sickest inmates in correctional institutions with the greatest on-site capabilities or those closest to a major medical center.

State corrections officials can choose to contract with some or all community hospitals near prisons or may concentrate inpatient treatment at one or two hospitals inside the state if geographically possible. While officials endeavour to keep off-site care within the state, the closest appropriate hospital may in some cases be in another state. Equally Jared Brunk, chief financial officeholder of the Illinois Department of Corrections, said, "Certain institutions are so [near] the edge that information technology is closer for inmates to go to another state for hospitalization services."

When States Build Their Own Prison house Hospitals

On the grounds of N Carolina's maximum security prison house near the state Capitol in Raleigh sits a five-story building that is rare in correctional health intendance. It is an on-site hospital with 120 inpatient medical/surgical beds and another 216 beds for those with mental affliction.

The General Assembly spent $180 million to build the medical heart and hired more than 300 employees to consolidate health care and inpatient hospitalization for many of the state's incarcerated adults. Opened in 2011, the infirmary was designed with security in heed. For the many patients coming for treatment at Cardinal Prison, elaborate off-site transportation planning is not needed. And since most are serving long sentences, they will probably need more medical intendance over the course of their stays than those serving shorter sentences.

Incarcerated individuals at the 54 other North Carolina institutions practice come to the Raleigh prison campus for nonemergency services, including ultrasounds, X-rays, CT scans, and same-twenty-four hour period surgical procedures. The state buses patients from facilities effectually the state to the Raleigh facility.20

Dissimilar Due north Carolina, Texas located its gratis-standing prison house hospital on the campus of the University of Texas Medical Branch in Galveston. Staffed by university employees and correctional officers, the pedagogy hospital includes 172 inpatient beds secured by a locked gate.21 Given the size of the land, nigh acute and emergency care is delivered at the hospital closest to the patient's prison, but in one case stabilized, he or she is transferred to the Galveston prison hospital.

Georgia also consolidates most specialized intendance at a land-owned infirmary in Grovetown that treats only incarcerated adults.

All 3 states have the potential to provide seamless intendance betwixt their prisons and hospitals. In Georgia and Texas, the aforementioned academy that provides virtually in-prison health intendance as well runs the correctional hospital, allowing for mutual protocols and easier coordination. North Carolina's corrections department oversees in-prison care and its defended infirmary. With the recent addition of electronic health records past the Texas corrections department, patient data can be shared effortlessly among settings.22

Some counties accept also constructed on-site correctional medical centers, allowing local jails to offering more expansive services. Dallas County, Texas, built a $50 million medical center at its jail, staffed by clinicians from its county prophylactic cyberspace wellness care provider, Parkland Hospital, to handle most inmates' health needs.23; And Los Angeles County congenital an urgent intendance middle at its jail to reduce infirmary bills and cutting transportation costs.24 After the LA facility opened, most five fewer patients a twenty-four hour period, on average, were sent to a hospital. After 6 months, the jail had saved over $1 million in transportation costs and a most identical amount from fewer visits.25

Transporting and securing correctional patients at hospitals

Moving someone betwixt a prison house and a community hospital and guarding them during treatment involves a unique set up of considerations. The geography of a land, the locations of its prisons and hospitals, and the preferences of country lawmakers all play a function in determining a corrections department'southward transportation and security strategy.

Underlying the planning for secure transportation and hospital security is the run a risk an incarcerated individual may effort to escape the vehicle or the infirmary, posing a threat to corrections staff, health intendance workers, and the community. Ane state corrections medical director recalled a prisoner fleeing ii officers in a community hospital. The facility was placed on lockdown until the escapee was recaptured. "The infirmary is non going to take that very well," he said.26 In 2017, a rape doubtable in Ohio overpowered a sheriff's deputy while existence transported betwixt a psychiatric hospital and the jail, stole the officer'due south gun, and fled after demanding that the deputy remove his leg shackles and handcuffs.27

The logistics of a infirmary trip are intricate.28 Many states take especially trained transportation units within the corrections department, supplemented past land or local police during staffing shortages. Security personnel at the prison and the hospital must be notified of the planned trip and the person's custody level—minimum, medium, or maximum. At least two officers unremarkably accompany an individual when he or she is being taken to a hospital. Distances betwixt correctional institutions and hospitals can be a challenge, specially during choppy weather condition. Alaska corrections officials, who usually send incarcerated individuals off-site in buses and vans, sometimes fly someone to a hospital on a charter or commercial flight.29 The arrangement between Texas' corrections department and the University of Texas Medical Branch includes a specialized core of nurses to handle the logistics of moving patients from hospitals around the state, where they are initially stabilized, to the country corrections department's hospital in Galveston.30

In one case at the hospital, the patient's security must exist coordinated between the land corrections system and the hospital. Several states, including Connecticut, Colorado, Louisiana, New York, New Jersey, Ohio, Texas,31 Virginia, and Wisconsin, accept converted, or "hardened," a floor or section of ane or more hospitals to an inmate-only wing for small procedures and noninvasive in- and outpatient care. For surgery and other specialized care, the person is transported to other public areas of the hospital but returned to the secure unit for ascertainment and recuperation. Hospital nurses and doctors staff such secure areas, but state correctional officers guard them. The hospital rooms are modified to meet strict security standards—including bolted-down boob tube sets and no windows or toilet seats—merely must yet encounter the rigorous standards of infirmary accrediting organizations. Although these units require a sizable upfront investment, they may be toll-effective over the long run compared with housing each sick adult in a unmarried room guarded by ii officers circular-the-clock.

Corrections officials written report that special training and scheduling add to hospitalization costs and challenges. Land corrections security personnel and country troopers transporting sick patients normally undergo preparation to prevent their guns from beingness grabbed. Infirmary security, nurses, doctors, and other personnel must besides be taught how to deliver intendance to incarcerated individuals who may be shackled and handcuffed during treatment.

When a patient must be moved off-site for nonurgent care and information technology can be scheduled in advance, state officials must arrange for transport and 24-hour-a-twenty-four hours security at the infirmary. This oft requires overtime pay because of chronic staff shortages.32

In Alaska, corrections officials have reported extensive overtime costs, a lack of relief staff, having to pull nontransportation officers off their shifts to accept patients to off-site medical visits, and staff turnover. "Despite the fact that thousands of staff hours are spent each month supervising inmates in outside community hospitals,facilities do non have defended posts for this function. As a result, facilities must reassign staff from critical facility posts to provide hospital supervision or rely on overtime to provide required supervision," officials said in a 2016 staffing assay.33 Virginia and Nevada corrections officials, amidst others, accept warned lawmakers that a shortage of officers has injure patient care.34 "Transport occurs, simply oft there are no officers to escort the patient to their appointments or procedures,"35 causing delays, officials said. The same staffing shortages can also postpone an private'due south timely discharge from a infirmary.

Paying the hospital bill

Corrections officials or vendors reimburse hospitals using a multifariousness of rates for inpatient and outpatient care. As correctional health care costs per inmate are ascension in many states, co-ordinate to Pew enquiry,36 state officials aim to pay the lowest rates possible without discouraging hospitals from providing care to those who are incarcerated. (Hospitals are legally required to accept and at least stabilize emergency patients merely can then terminate treatment.)

Corrections officials often endeavor to piggyback on an existing fee schedule or a percentage thereof, such equally the one used by their state Medicaid bureau,37 the federal Medicare program,38 the land employee health insurance plan,39 or a large insurer's negotiated rates.40 States that concentrate off-site intendance at one or 2 hospitals have unlike considerations, given their volume, than corrections departments that use hospitals throughout their state, since the latter'due south effect on any one hospital is somewhat diluted. Similarly, states that invest in hardening a unit at a infirmary must ensure that the corrections department and the hospital are both satisfied with the rates since corrections officials cannot easily move the intendance to some other facility without wasting the state'south investment in the infrastructure modifications. Texas—which has both a corrections section-only hospital in Galveston, in the southern part of the state, and a hardened unit at a infirmary in East Texas—reported that opening the latter unit non only benefited prisoners, only the volume of patients from correctional facilities likewise has helped stabilize the finances of this rural infirmary.41

Because a land'south Medicaid program typically negotiates the everyman rates of whatsoever payer in a state, a corrections department that uses this fee schedule unremarkably pays less for services than corrections departments in states that use other schedules. Agencies that use a Medicaid or Medicare rate do so regardless of the patient's insurance status. Usage simply relieves the corrections section from having to negotiate its own rates.

Given the significant accommodations that must be made when treating incarcerated individuals, hospitals may seek a premium over the Medicaid charge per unit. Some corrections departments and private vendors are willing to pay this fee, especially if the hospital locks in a contract with them. For example, in improver to paying the Medicaid rate, New Bailiwick of jersey's section of corrections pays a hospital a fixed monthly supplement for these costs. Mississippi's corrections department pays hospitals 200 percent of Medicaid rates for inpatient care, partly in recognition of the special conditions imposed on the staff by such patients, and as an incentive for the institution to willingly accept them. If the hospital or specialist does not have a contract with the corrections department, the state reimburses at only 100 percent of the Medicaid rate. Laws in Utah and Due north Carolina also require that a lower charge per unit exist paid to hospitals that do not contract with their corrections departments. New York does the same, although the practice is not required by state law.

Medicaid expansion has helped cut costs

The ACA allowed states to expand their eligibility criteria for Medicaid coverage for all individuals nether age 65 who earn upwardly to 138 pct of the federal poverty level ($16,643 for a unmarried adult in 2017).42 This expansion made many more incarcerated individuals eligible for Medicaid coverage, as income for nearly all falls below this threshold while they are in jail or prison. 30-1 states and the District of Columbia take expanded their criteria in accord with the ACA.

States take never been precluded from enrolling those who are incarcerated in Medicaid. All the same, most of these individuals historically could non enroll because, as nondisabled adults without dependent children, they did not see many states' eligibility criteria despite their low income.

States may not provide Medicaid coverage for health intendance services provided to incarcerated individuals unless the care is delivered exterior of correctional facilities, such as at a hospital, and the eligible adult has been admitted for 24 hours or more.43 In these cases, country Medicaid agencies can obtain federal reimbursement that covers at least half of off-site inpatient costs—and substantially more if the person is newly eligible—equally long every bit he or she is enrolled at the time of the hospitalization or shortly thereafter.

This policy change has caused a large shift of eligible inpatient infirmary costs from state corrections agencies to the Medicaid plan. It has also immune expansion states that apply contracted vendors—and that, like Massachusetts, concord those vendors financially at take a chance for off-site inpatient care—to lower their capitation rate.44

Officials in states that expanded Medicaid say they have achieved millions of dollars in savings because most corrections hospitalizations accept qualified for coverage. Alaska and Ohio are among states that reported meaning correctional cost savings due to ACA expansion.

Some state corrections departments too benefited past shifting the processing of hospital claims to their state Medicaid agencies, which is required earlier challenge federal matching funds. After Nevada and Indiana expanded their eligibility, both turned over their billing operations for inpatient intendance to their Medicaid agencies. This relieved corrections officials of a function that Medicaid agencies routinely had carried out.

Georgia, Northward Carolina, and Texas, the states that operate a corrections-only hospital for most of their off-site prison house care, are not able to accuse the Medicaid program when a prisoner is admitted to one of these hospitals considering they are not open to the public, a condition for Medicaid participation.45 However, that exclusion is of less business to these states considering none has expanded Medicaid eligibility nether the ACA.

Promising approaches to reducing costs

While states will always have to send some prisoners to hospitals, corrections officials tin can reduce inpatient stays and costs by expanding programs such as telemedicine and mobile services. Past examining people by video or in a mobile van, doctors may be able to diagnose illnesses and injuries and prevent a trip to the hospital.

Texas arranges eleven,000 patient-doctor video conferences a month—second only to the U.S. military.46 Telemedicine produces savings by reducing the demand for transportation and staff supervision.An off-site medical specialist may as well help to identify subtle medical issues that might otherwise be overlooked, resulting in improved intendance and fewer emergency room visits.47

In improver to cutting transportation and security costs, this use of technology gives corrections departments more than pick of specialists. Several state corrections departments reported challenges recruiting clinicians stemming from prisons' often remote locations and the correctional surroundings itself. These variables either drive up what corrections departments must pay to recruit and retain skilled clinicians or extend the fourth dimension and endeavour required to fill each vacancy. Widening the field of potential medical consultants gives the state a stronger negotiating position on compensation costs. Telemedicine also provides an opportunity for a prison's main intendance provider to participate in a video session with a medical specialist and patient, improving the coordination of care.

Corrections agencies in Southward Carolina and Wisconsin are partnering with their state universities to deport out telemedicine programs. "Nosotros're buying some new equipment that actually can practise heart sounds and lung sounds and EKGs," and the results can be sent direct to the subspecialist, said James Greer, director of the Wisconsin Corrections Department'south Bureau of Health Services.

Other states are bringing mobile technology to prisons, saving them the toll and logistics of having to transport patients to hospitals or other off-site diagnostic facilities. Ane such use is mammography. A number of states periodically charter a mobile mammography van to administer these screening tests.48 When Montana sent a mobile van to its women's prison in 2016, some of the individuals said it was the offset time they had had the procedure.49

Some other way to reduce inpatient hospital days is to set up palliative care and hospice programs within prisons for those who are dying, forth with a procedure for compassionate release.50 However, some states study difficulty finding suitable customs placements for people who are sick enough to authorize.51

Conclusion

State corrections departments will always need to send people in their prison house systems off-site for specialized care. This study shows the complexity of arranging for and managing such services,whether the department or a private vendor oversees them.

State policymakers must go along to expect for ways to trim costs, especially as their prison population ages and requires more intensive and frequent care. Periodically, corrections officials should evaluate the expense of using specialized services off-site instead of on-site. But off-site care will ever accept to be designed—and have its costs analyzed—inside the context of an effective and efficient prison house health intendance system. Understanding how other country corrections departments adapt and pay for hospital care tin assist policymakers make ameliorate decisions on this of import and expensive category of care.

Endnotes

- Jeremy Travis, Bruce Western, and Steve Redburn, eds., The Growth of Incarceration in the United states: Exploring Causes and Consequences (Washington: National Research Council, 2014), 216, https://www.nap.edu/read/18613/chapter/1; Douglas C. McDonald, "Medical Care in Prisons," Criminal offense and Justice 26 (1999): 427–78, http://www.journals.uchicago.edu/doi/abs/10.1086/449301.

- McDonald, "Medical Care in Prisons," 443–44.

- The Pew Charitable Trusts, "Land Prison Health Intendance Spending" (July 2014), http://www.pewtrusts.org/~/media/avails/2014/07/stateprisonhealthcarespendingreport.pdf; New York data were reported for fiscal 2015. Virginia data were reported for fiscal 2016.

- AARP, "Chronic Atmospheric condition Among Older Americans," https://assets.aarp.org/rgcenter/wellness/beyond_50_hcr_conditions.pdf.

- Ibid.

- The Pew Charitable Trusts, "Prison Health Care: Costs and Quality" (October 2017), http://www.pewtrusts.org/~/media/assets/2017/10/sfh_prison_health_care_costs_and_quality_final.pdf.

- Stephen Weiss, "Medical Care Provided in Land Prisons—Report of the Costs" (presented at the Articulation Commission on Health Care coming together, October. 5, 2016), http://jchc.virginia.gov/four.%20Medical%20Care%20Provided%20in%20State%20Prisons%20CLR.pdf.

- Ibid.

- The Pew Charitable Trusts, "Prison house Wellness Intendance: Costs and Quality."

- Lettie Prell (onetime managing director of inquiry, Iowa Department of Corrections), interview with The Pew Charitable Trusts, Aug. 29, 2016.

- Mark Looney (senior budget examiner, New York State Division of the Upkeep), interview with The Pew Charitable Trusts, Feb. 21, 2018.

- Pew interviews with state corrections officials; Montana Section of Corrections, "Level of Therapeutic Care," sec. 4-B, last modified May 30, 2017, http://cor.mt.gov/Portals/104/Resource/Policy/Chapter4/4-five-10%20Level%20of%20Therapeutic%20Care%2005.30.17.pdf.

- InterQual Criteria (McKesson) (https://www.changehealthcare.com/solutions/interqual) and Milliman Care Guidelines (https://www.mcg.com/intendance-guidelines/care-guidelines) are typically used to document the "standard of care" by utilization review staff to justify referrals and to support the level of care and intendance management of complex and/or serious wellness conditions.

- Hawaii Department of Public Safety, "Infirmary and Specialty Intendance," Oct. 20, 2015, https://dps.hawaii.gov/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/COR.ten.1D.05.pdf.

- State of Connecticut, "Memorandum of Agreement Betwixt Connecticut Department of Corrections and Academy of Connecticut Wellness Eye for the Provision of Health Services to Inmate Patients" (August 2012), 23, 30, 41.

- The California corrections department defined readmission equally the pct of community hospitalizations that were linked to a previous hospitalization for the same patient with no more than xxx days between the two episodes of care. They excluded hospitalizations for scheduled aftercare such as chemotherapy and sure other circumstances.

- Clarence Cryer Jr., "Reducing Infirmary Readmissions Among Incarcerated Patients,"Journal of Correctional Health Care 24, no. one (2018): v, http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1078345817745054.

- Karah Gunther, executive director of government relations and health policy, Virginia Commonwealth Academy and the VCU Health System, pers. comm. to The Pew Charitable Trusts, Nov. 22, 2017.

- Florida Department of Corrections, Office of Health Services, "Utilization Direction Procedures" (March 17, 2015), 2, http://www.dc.state.fl.the states/business/HealthSvcs/Bulletins/15-09-4current.pdf.

- Terri Catlett (deputy manager, prison wellness services, N Carolina Section of Public Safety), interview with The Pew Charitable Trusts, August 2016; Due north Carolina Section of Public Prophylactic, "New Prison house Medical Facilities," accessed Feb. ane, 2018,http://www.doctor.country.nc.us/DOP/health/new_facilities.html; Joe Watson, "New North Carolina Medico Hospital Promises Amend Healthcare for Prisoners," Prison Legal News, December. 15, 2012, https://www.prisonlegalnews.org/news/2012/december/xv/new-north-carolina-doc-hospital-promises-meliorate-healthcare-for-prisoners; North Carolina Department of Public Rubber, Division of Developed Correction, "Research Bulletin," accessed Feb. ane, 2018, https://randp.doc.state.nc.us/pubdocs/0007078.PDF.

- University of Texas Medical Branch, "UTMB TDCJ Hospital: Mission and Overview," accessed Dec. 17, 2017, https://www.utmb.edu/tdcj/mission.asp.

- Electronic Signature & Records Clan, "Electronic Health Records Change the Game for Texas' Prison house System," Aug. 25, 2016, https://esignrecords.org/news-electronic-health-records-modify-game-texas-prison-system; Michael Ollove, "State Prisons Turn to Telemedicine to Improve Health and Save Money," Stateline, Jan. 21, 2016, http://www.pewtrusts.org/en/research-and-analysis/blogs/stateline/2016/01/21/country-prisons-plough-to-telemedicine-to-ameliorate.

- The Pew Charitable Trusts, "Jails: Inadvertent Wellness Care Providers" (January 2018), 17, http://www.pewtrusts.org/en/research-and-analysis/reports/2018/01/jails-inadvertent-health-care-providers.

- Erick Eiting et al., "Reduction in Jail Emergency Section Visits and Closure After Implementation of On-Site Urgent Care," Journal of Correctional Health Intendance 23, no. 1 (2017), http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/1078345816685563.

- Ibid.

- A state department of corrections medical director, interview with The Pew Charitable Trusts, Sept. 21, 2016.

- WRC-Tv, "Federal Officials Join Search for Ohio Rape Suspect Who Escaped," last modified Aug. 6, 2017, https://world wide web.nbcwashington.com/news/national-international/Prisoner-Charged-with-Rape-Overpowers-Deputy-Steals-His-Gun--438800833.html?amp=y.

- Arizona Department of Corrections, "Inmate Transportation," Department Society Manual, effective Nov. 19, 2012, https://corrections.az.gov/sites/default/files/policies/700/0705u.pdf.

- Alaska Department of Corrections, "System Staffing Analysis" (Feb. ix, 2016), 219, http://www.right.state.ak.the states/doc/corrections-staffing-written report.pdf.

- John Pulvino (senior director, quality and outcomes, Academy of Texas Medical Co-operative), interviews with The Pew Charitable Trusts, June 30, 2017, July 28, 2017, and March xvi, 2018.

- Texas has made this secure unit of measurement arrangement with a community hospital in Huntsville to supplement its inmate-only hospital in Galveston, which serves the majority of Texas inmates. Pulvino, interview.

- American Correctional Association, "Standards," accessed Nov. 12, 2017, http://www.aca.org/ACA_Prod_IMIS/ACA_Member/Standards___Accreditation/Standards/ACA_Member/Standards_and_Accreditation/StandardsInfo_Home.aspx?hkey=7c1b31e5-95cf-4bde-b400-8b5bb32a2bad; Virginia Commonwealth University, "VCU Health and the Department of Corrections" (presentation to the Virginia Senate Finance Committee, Virginia Commonwealth University, Aug. 25, 2016), http://sfc.virginia.gov/pdf/Public%20Safety/2016/Interim/082516_GuntherPresentation.pdf; Oklahoma Department of Corrections, "Transportation of Inmates," effective Oct. xx, 2016, http://doc.ok.gov/Websites/doctor/Images/Documents/Policy/op040111.pdf; Oklahoma Department of Corrections, "Security of Inmates in Non-Prison Hospitals," effective April 11, 2018, http://doc.ok.gov/Websites/doc/Images/Documents/Policy/op040114.pdf.

- Alaska Department of Corrections, "System Staffing Analysis," 220.

- Sean Whaley, "Nevada Dept. of Corrections Paid $fifteen.5M in OT in Fiscal 2017," Las Vegas Review-Journal, Sept. 12, 2017, https://world wide web.reviewjournal.com/local/local-nevada/nevada-dept-of-corrections-paid-15-5m-in-ot-in-financial-2017; Ramona Giwargis, "Policy Modify Could Save Nevada Prisons Millions in Overtime Pay," Las Vegas Review-Journal,Feb. 15, 2018, https://world wide web.reviewjournal.com/news/politics-and-authorities/nevada/policy-change-could-save-nevada-prisons-millions-in-overtime-pay.

- Virginia Commonwealth Academy, "VCU Wellness."

- The Pew Charitable Trusts, "Prison Health Intendance: Costs and Quality."

- For example, Maine, North Dakota, Texas, Washington, and West Virginia.

- For example, Indiana, Wisconsin, and Wyoming.

- For instance, Alabama and Due south Carolina.

- Virginia, for example.

- Pulvino, interview.

- U.S. Section of Health and Human Services, "U.S. Federal Poverty Guidelines Used to Determine Financial Eligibility for Certain Federal Programs," accessed Feb. xv, 2017, https://aspe.hhs.gov/poverty-guidelines; Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, "Updated Guidance to Surveyors on Federal Requirements for Providing Services to Justice Involved Individuals" (Dec. 23, 2016), https://world wide web.cms.gov/Medicare/Provider-Enrollment-and-Certification/SurveyCertificationGenInfo/Downloads/Survey-and-Cert-Letter of the alphabet-xvi-21.pdf.

- The Pew Charitable Trusts, "How and When Medicaid Covers People Nether Correctional Supervision" (August 2016), http://www.pewtrusts.org/en/inquiry-and-analysis/event-briefs/2016/08/how-and-when-medicaid-covers-people-under-correctional-supervision.

- Jeffrey Fisher (director of contract compliance, Massachusetts Department of Correction), interview with The Pew Charitable Trusts, Oct.19, 2016.

- The Pew Charitable Trusts, "How and When Medicaid Covers People."

- Pulvino, interview.

- Karen C. Fox, Grant West. Somes, and Teresa Yard. Waters, "Timeliness and Access to Healthcare Services via Telemedicine for Adolescents in State Correctional Facilities," Periodical of Boyish Health 41, no. 2 (2007): 161–67, http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2007.05.001.

- Karishma A. Chari et al., "National Survey of Prison Health Intendance: Selected Findings," National Health Statistics Reports 96 (2016): 8, https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nhsr/nhsr096.pdf.

- Billings Gazette,"How Medicaid Can Help Reduce Montana's Prison house, Jail Crowding," Aug. 14, 2016, https://billingsgazette.com/print-specific/cavalcade/gazette-stance-how-medicaid-can-help-reduce-montana-s-prison/article_694dc50b-ef8d-5af2-9d48-6b6a8adcf27e.html.

- Adam Wisnieski, "'Model' Nursing Home for Paroled Inmates to Go Federal Funds," Connecticut Health I-Team, April 25, 2017, http://c-hit.org/2017/04/25/model-nursing-dwelling-for-paroled-inmates-to-go-federal-funds; Prell interview.

- David Drury, "Feds: No Medicaid Reimbursement for Prisoners at Rocky Hill Nursing Home,"Hartford Courant, Sept. five, 2015, http://www.courant.com/community/rocky-loma/hc-rocky-hill-nursing-home-0905-20150904-story.html.

Boosted RESOURCES

MORE FROM PEW

Source: https://www.pewtrusts.org/en/research-and-analysis/reports/2018/07/19/state-prisons-and-the-delivery-of-hospital-care

Posted by: trainorwimen1956.blogspot.com

0 Response to "Does A Rich Entrepreneur Or An Inmate In A State Prison Have Access To Services That Others Lack?"

Post a Comment