In The Long Run, What Determines The Level Of Total Production Of Goods And Services In An Economy?

9.2 Output Conclusion in the Short Run

Learning Objectives

- Prove graphically how an private business firm in a perfectly competitive market can utilise total revenue and total toll curves or marginal revenue and marginal cost curves to determine the level of output that volition maximize its economic profit.

- Explain when a business firm will close down in the short run and when it will operate even if it is incurring economic losses.

- Derive the firm'southward supply curve from the business firm's marginal toll curve and the industry supply curve from the supply curves of private firms.

Our goal in this department is to see how a firm in a perfectly competitive market determines its output level in the short run—a planning menstruation in which at least ane factor of product is fixed in quantity. We shall see that the firm tin maximize economic profit by applying the marginal decision dominion and increasing output up to the point at which the marginal do good of an additional unit of measurement of output is just equal to the marginal cost. This fact has an important implication: over a wide range of output, the business firm'south marginal cost curve is its supply curve.

Price and Acquirement

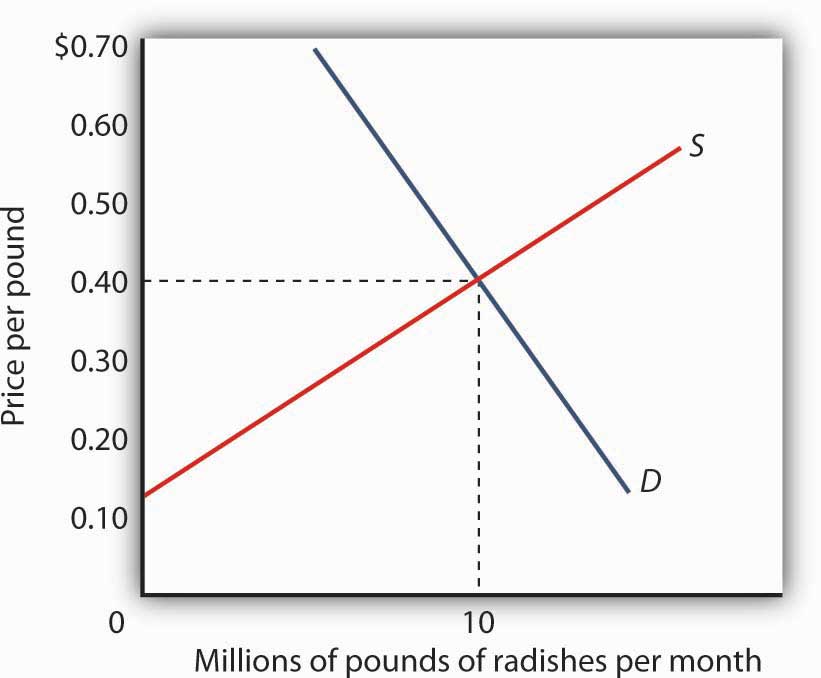

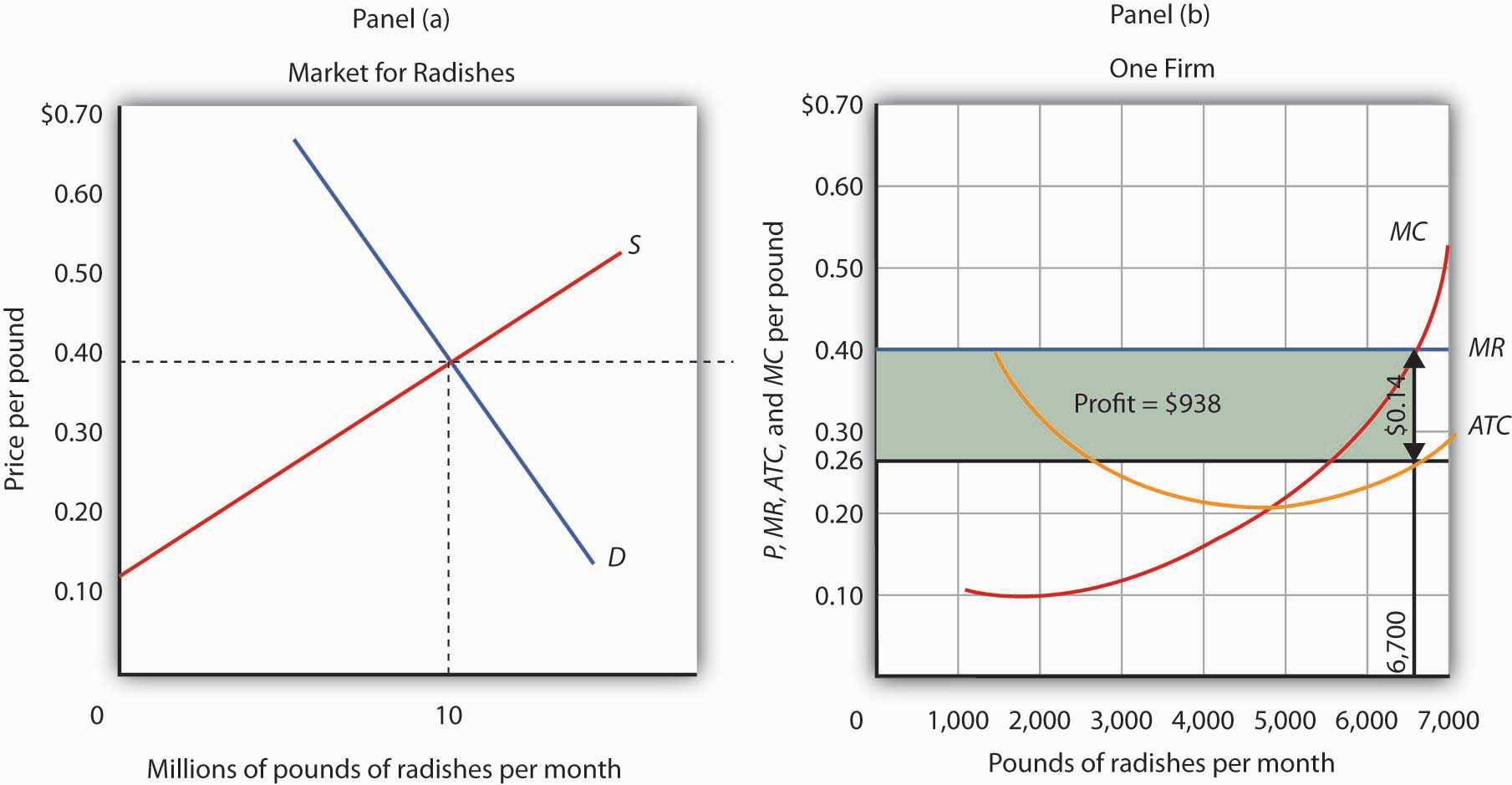

Each firm in a perfectly competitive market is a cost taker; the equilibrium price and industry output are determined by demand and supply. Figure ix.3 "The Market for Radishes" shows how demand and supply in the market for radishes, which we shall assume are produced nether conditions of perfect competition, decide total output and price. The equilibrium price is $0.40 per pound; the equilibrium quantity is x million pounds per month.

Figure 9.3 The Market for Radishes

Price and output in a competitive marketplace are adamant past demand and supply. In the market for radishes, the equilibrium toll is $0.40 per pound; 10 1000000 pounds per month are produced and purchased at this price.

Because it is a price taker, each firm in the radish industry assumes it tin can sell all the radishes it wants at a price of $0.40 per pound. No affair how many or how few radishes it produces, the firm expects to sell them all at the market place cost.

The assumption that the business firm expects to sell all the radishes it wants at the market cost is crucial. If a firm did non expect to sell all of its radishes at the marketplace price—if information technology had to lower the price to sell some quantities—the firm would non be a price taker. And toll-taking behavior is central to the model of perfect competition.

Radish growers—and perfectly competitive firms in general—have no reason to accuse a cost lower than the market price. Because buyers have complete data and because we assume each firm's product is identical to that of its rivals, firms are unable to accuse a cost higher than the market cost. For perfectly competitive firms, the price is very much like the weather: they may complain virtually it, merely in perfect contest there is nothing whatsoever of them can do about it.

Total Revenue

While a firm in a perfectly competitive market has no influence over its price, information technology does determine the output it volition produce. In selecting the quantity of that output, one important consideration is the revenue the firm will gain by producing it.

A firm's total revenue is establish past multiplying its output past the cost at which it sells that output. For a perfectly competitive firm, full revenue (TR) is the market price (P) times the quantity the firm produces (Q), or

Equation 9.1

[latex]TR = P \times Q[/latex]

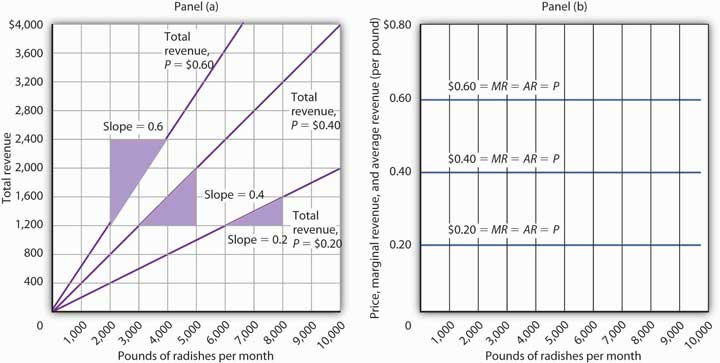

The relationship betwixt market place price and the business firm's total revenue curve is a crucial i. Console (a) of Figure 9.4 "Full Revenue, Marginal Acquirement, and Average Revenue" shows total revenue curves for a radish grower at three possible market prices: $0.20, $0.forty, and $0.60 per pound. Each total revenue curve is a linear, upward-sloping curve. At whatsoever price, the greater the quantity a perfectly competitive firm sells, the greater its total revenue. Notice that the greater the price, the steeper the full revenue curve is.

Figure 9.4 Total Acquirement, Marginal Revenue, and Average Revenue

Panel (a) shows dissimilar total revenue curves for three possible market prices in perfect competition. A full revenue curve is a direct line coming out of the origin. The slope of a total revenue curve is MR; it equals the market price (P) and AR in perfect competition. Marginal revenue and average revenue are thus a unmarried horizontal line at the market place price, as shown in Panel (b). There is a different marginal revenue curve for each price.

Price, Marginal Revenue, and Average Revenue

The slope of a total revenue bend is particularly important. Information technology equals the change in the vertical axis (total revenue) divided by the change in the horizontal axis (quantity) between any 2 points. The slope measures the rate at which total acquirement increases as output increases. We can call back of it as the increase in total revenue associated with a 1-unit increase in output. The increase in full revenue from a 1-unit increase in quantity is marginal acquirement. Thus marginal revenue (MR) equals the slope of the total revenue bend.

How much additional revenue does a radish producer gain from selling i more than pound of radishes? The answer, of course, is the market price for 1 pound. Marginal revenue equals the market toll. Because the marketplace price is not affected by the output choice of a single firm, the marginal acquirement the house gains by producing i more unit is always the market price. The marginal acquirement curve shows the relationship betwixt marginal revenue and the quantity a firm produces. For a perfectly competitive firm, the marginal revenue curve is a horizontal line at the marketplace price. If the market toll of a pound of radishes is $0.40, then the marginal acquirement is $0.twoscore. Marginal revenue curves for prices of $0.twenty, $0.40, and $0.lx are given in Panel (b) of Figure 9.four "Total Acquirement, Marginal Revenue, and Average Revenue". In perfect competition, a house's marginal revenue curve is a horizontal line at the market price.

Cost also equals average acquirement, which is total revenue divided by quantity. Equation 9.1 gives total revenue, TR. To obtain boilerplate revenue (AR), nosotros carve up total acquirement by quantity, Q. Because full revenue equals price (P) times quantity (Q), dividing by quantity leaves us with price.

Equation nine.2

[latex]AR = \frac{TR}{Q} = \frac{P \times Q}{Q} = P[/latex]

The marginal revenue curve is a horizontal line at the market price, and boilerplate revenue equals the market price. The average and marginal revenue curves are given by the same horizontal line. This is consequent with what we take learned about the human relationship between marginal and boilerplate values. When the marginal value exceeds the average value, the average value will exist ascension. When the marginal value is less than the average value, the average value volition be falling. What happens when the average and marginal values practise not change, equally in the horizontal curves of Panel (b) of Figure 9.4 "Total Revenue, Marginal Revenue, and Average Revenue"? The marginal value must equal the boilerplate value; the ii curves coincide.

Marginal Acquirement, Cost, and Demand for the Perfectly Competitive Business firm

We accept seen that a perfectly competitive firm'due south marginal revenue curve is just a horizontal line at the market price and that this same line is also the house's average revenue curve. For the perfectly competitive house, MR=P=AR. The marginal revenue curve has some other meaning besides. It is the need curve facing a perfectly competitive firm.

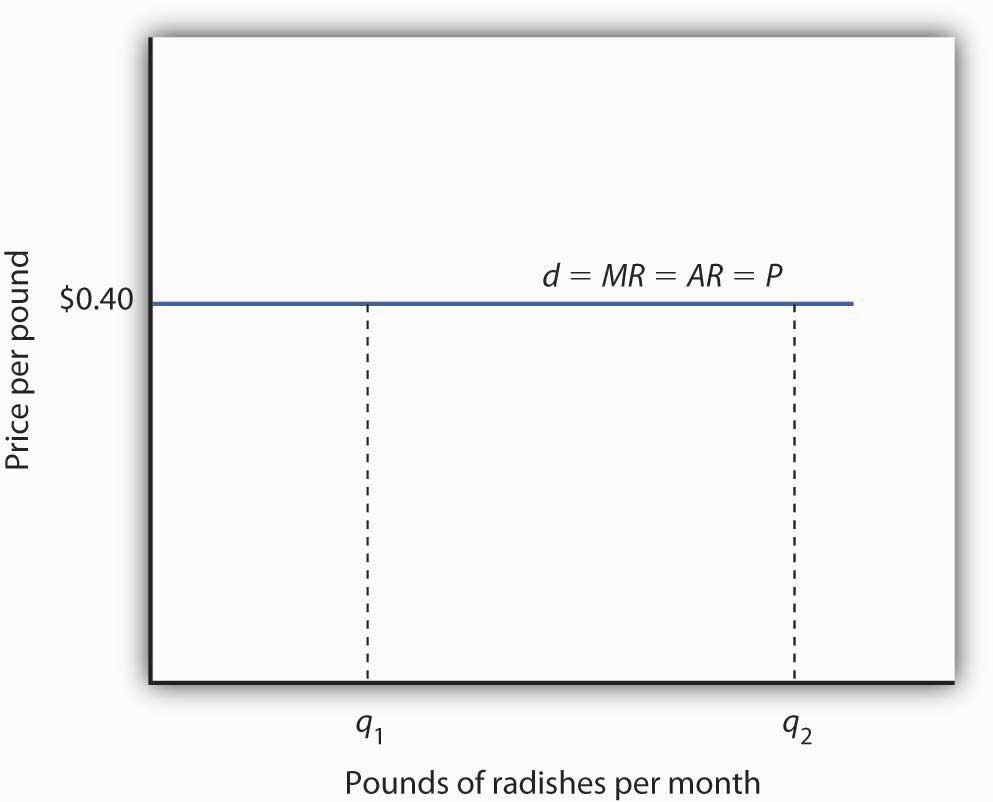

Consider the instance of a single radish producer, Tony Gortari. We assume that the radish market is perfectly competitive; Mr. Gortari runs a perfectly competitive house. Suppose the market price of radishes is $0.xl per pound. How many pounds of radishes can Mr. Gortari sell at this price? The reply comes from our assumption that he is a cost taker: He can sell any quantity he wishes at this price. How many pounds of radishes will he sell if he charges a price that exceeds the marketplace toll? None. His radishes are identical to those of every other house in the market, and everyone in the market place has complete information. That means the demand curve facing Mr. Gortari is a horizontal line at the market price as illustrated in Figure 9.5 "Price, Marginal Revenue, and Need". Notice that the curve is labeled d to distinguish information technology from the market place demand bend, D, in Figure ix.3 "The Marketplace for Radishes". The horizontal line in Figure 9.5 "Toll, Marginal Revenue, and Demand" is likewise Mr. Gortari's marginal revenue curve, MR, and his boilerplate acquirement curve, AR. It is too the marketplace toll, P.

Of grade, Mr. Gortari could accuse a price beneath the market toll, but why would he? We assume he tin sell all the radishes he wants at the market toll; there would be no reason to charge a lower price. Mr. Gortari faces a demand bend that is a horizontal line at the market cost. In our subsequent analysis, we shall refer to the horizontal line at the market cost merely equally marginal revenue. Nosotros should remember, however, that this aforementioned line gives u.s. the market cost, average revenue, and the demand curve facing the firm.

Effigy ix.v Cost, Marginal Revenue, and Need

A perfectly competitive firm faces a horizontal demand curve at the marketplace price. Here, radish grower Tony Gortari faces need bend d at the market price of $0.40 per pound. He could sell q 1 or q two—or any other quantity—at a price of $0.40 per pound.

More than by and large, nosotros can say that any perfectly competitive firm faces a horizontal demand curve at the market price. Nosotros saw an instance of a horizontal demand curve in the affiliate on elasticity. Such a curve is perfectly elastic, significant that any quantity is demanded at a given price.

Economical Profit in the Brusque Run

A firm's economic turn a profit is the difference between total revenue and total cost. Remember that total price is the opportunity price of producing a certain proficient or service. When we speak of economic profit we are speaking of a firm's total revenue less the total opportunity price of its operations.

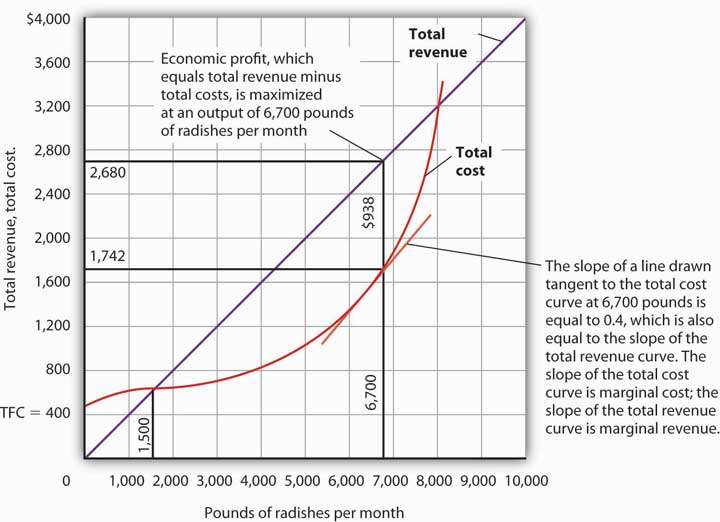

As we learned, a firm's total cost curve in the brusk run intersects the vertical centrality at some positive value equal to the house's total fixed costs. Total price then rises at a decreasing rate over the range of increasing marginal returns to the house's variable factors. It rises at an increasing rate over the range of diminishing marginal returns. Figure ix.six "Total Acquirement, Total Cost, and Economic Turn a profit" shows the total toll curve for Mr. Gortari, as well as the full revenue curve for a toll of $0.40 per pound. Suppose that his total stock-still cost is $400 per calendar month. For any given level of output, Mr. Gortari's economic turn a profit is the vertical altitude between the total revenue curve and the total cost bend at that level.

Figure 9.six Total Revenue, Total Cost, and Economical Turn a profit

Economical profit is the vertical altitude betwixt the total revenue and total cost curves (revenue minus costs). Here, the maximum profit attainable by Tony Gortari for his radish production is $938 per calendar month at an output of vi,700 pounds.

Allow us examine the total revenue and total cost curves in Effigy nine.half dozen "Total Revenue, Total Cost, and Economic Profit" more advisedly. At zip units of output, Mr. Gortari's total cost is $400 (his total stock-still toll); total revenue is zero. Total toll continues to exceed total revenue upwards to an output of one,500 pounds per month, at which point the two curves intersect. At this bespeak, economic profit equals zip. As Mr. Gortari expands output in a higher place 1,500 pounds per month, full acquirement becomes greater than total cost. We see that at a quantity of one,500 pounds per calendar month, the total revenue curve is steeper than the total cost curve. Because revenues are rising faster than costs, profits rise with increased output. As long as the full acquirement curve is steeper than the total toll curve, profit increases every bit the firm increases its output.

The total revenue curve'southward slope does non change as the business firm increases its output. But the total toll curve becomes steeper and steeper equally diminishing marginal returns set in. Somewhen, the total cost and total revenue curves will accept the same gradient. That happens in Figure 9.vi "Total Revenue, Total Toll, and Economical Profit" at an output of 6,700 pounds of radishes per month. Detect that a line drawn tangent to the total price curve at that quantity has the same slope every bit the total revenue curve.

As output increases beyond vi,700 pounds, the total cost curve continues to get steeper. It becomes steeper than the full revenue curve, and profits fall as costs rise faster than revenues. At an output slightly above 8,000 pounds per month, the total revenue and cost curves intersect again, and economic profit equals zero. Mr. Gortari achieves the greatest profit possible by producing 6,700 pounds of radishes per month, the quantity at which the full cost and full revenue curves have the same slope. More than more often than not, we can conclude that a perfectly competitive house maximizes economic turn a profit at the output level at which the total revenue curve and the full cost curve take the same slope.

Applying the Marginal Decision Rule

The gradient of the total revenue curve is marginal acquirement; the slope of the total cost curve is marginal price. Economic profit, the departure between full revenue and total price, is maximized where marginal revenue equals marginal cost. This is consistent with the marginal determination dominion, which holds that a profit-maximizing firm should increase output until the marginal do good of an additional unit of measurement equals the marginal cost. The marginal benefit of selling an additional unit is measured every bit marginal revenue. Finding the output at which marginal revenue equals marginal toll is thus an awarding of our marginal determination dominion.

Figure 9.vii "Applying the Marginal Decision Rule" shows how a firm can utilize the marginal decision rule to determine its profit-maximizing output. Panel (a) shows the market place for radishes; the market place need curve (D), and supply curve (Due south) that we had in Figure nine.3 "The Market place for Radishes"; the market price is $0.40 per pound. In Panel (b), the MR curve is given by a horizontal line at the marketplace price. The firm'due south marginal cost curve (MC) intersects the marginal revenue bend at the bespeak where profit is maximized. Mr. Gortari maximizes profits past producing half-dozen,700 pounds of radishes per month. That is, of course, the result we obtained in Effigy 9.six "Total Acquirement, Total Cost, and Economic Profit", where we saw that the firm's total revenue and total cost curves differ by the greatest amount at the bespeak at which the slopes of the curves, which equal marginal revenue and marginal cost, respectively, are equal.

Figure 9.seven Applying the Marginal Decision Rule

The market toll is determined past the intersection of demand and supply. Equally always, the firm maximizes profit by applying the marginal decision rule. It takes the market price, $0.40 per pound, equally given and selects an output at which MR equals MC. Economic profit per unit is the difference between ATC and price (here, $0.xiv per pound); economical profit is profit per unit times the quantity produced ($0.14 × 6,700 = $938).

Nosotros can use the graph in Figure ix.vii "Applying the Marginal Conclusion Rule" to compute Mr. Gortari's economic profit. Economic turn a profit per unit is the difference betwixt toll and average total cost. At the profit-maximizing output of 6,700 pounds of radishes per month, average total price (ATC) is $0.26 per pound, as shown in Console (b). Cost is $0.twoscore per pound, so economic profit per unit is $0.fourteen. Economical turn a profit is found by multiplying economic profit per unit by the number of units produced; the firm'south economic profit is thus $938 ($0.14 × vi,700). Information technology is shown graphically by the surface area of the shaded rectangle in Panel (b); this expanse equals the vertical distance between marginal revenue (MR) and average total cost (ATC) at an output of 6,700 pounds of radishes times the number of pounds of radishes produced, 6,700, in Effigy 9.vii "Applying the Marginal Determination Rule".

Heads Up!

Await advisedly at the rectangle that shows economical profit in Panel (b) of Figure 9.7 "Applying the Marginal Decision Rule". It is found by taking the profit-maximizing quantity, half dozen,700 pounds, then reading up to the ATC curve and the firm'south need curve at the market cost. Economic turn a profit per unit of measurement equals price minus average total cost (P − ATC).

The firm's economic profit equals economic profit per unit times the quantity produced. It is found past extending horizontal lines from the ATC and MR curve to the vertical axis and taking the surface area of the rectangle formed.

There is no reason for the turn a profit-maximizing quantity to correspond to the lowest point on the ATC bend; it does non in this case. Students sometimes make the error of calculating economical profit as the difference between the cost and the lowest point on the ATC curve. That gives us the maximum economical profit per unit, but nosotros assume that firms maximize economic profit, non economic profit per unit of measurement. The firm's economical profit equals economic turn a profit per unit times quantity. The quantity that maximizes economic profit is determined by the intersection of ATC and MR.

Economic Losses in the Short Run

In the short run, a house has 1 or more inputs whose quantities are fixed. That means that in the short run the firm cannot go out its industry. Even if it cannot cover all of its costs, including both its variable and fixed costs, going entirely out of business is not an choice in the short run. The firm may close its doors, but information technology must continue to pay its stock-still costs. It is forced to accept an economic loss, the amount by which its total cost exceeds its full revenue.

Suppose, for instance, that a manufacturer has signed a 1-yr charter on some equipment. It must make payments for this equipment during the term of its lease, whether it produces anything or not. During the flow of the charter, the payments represent a stock-still price for the firm.

A firm that is experiencing economic losses—whose economic profits accept become negative—in the short run may either go on to produce or shut down its operations, reducing its output to zero. It will choose the option that minimizes its losses. The crucial test of whether to operate or close downwardly lies in the relationship between toll and average variable toll.

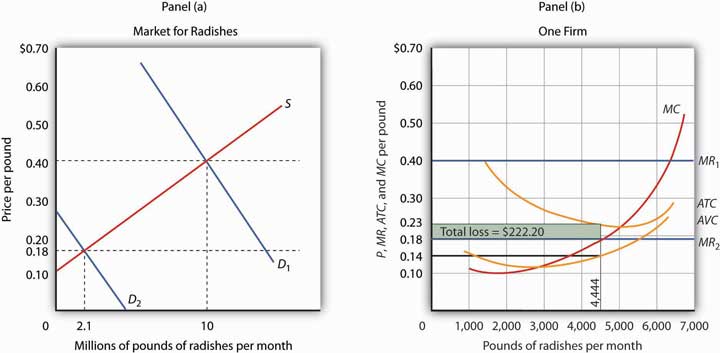

Producing to Minimize Economic Loss

Suppose the demand for radishes falls to D 2, as shown in Panel (a) of Effigy 9.8 "Suffering Economic Losses in the Brusk Run". The market place cost for radishes plunges to $0.eighteen per pound, which is below average total price. Consequently Mr. Gortari experiences negative economic profits—a loss. Although the new market cost falls brusque of average full cost, information technology all the same exceeds average variable cost, shown in Panel (b) as AVC. Therefore, Mr. Gortari should continue to produce an output at which marginal price equals marginal acquirement. These curves (labeled MC and MR two) intersect in Panel (b) at an output of 4,444 pounds of radishes per month.

Figure 9.eight Suffering Economic Losses in the Brusk Run

Tony Gortari experiences a loss when price drops below ATC, as it does in Panel (b) as a result of a reduction in demand. If price is above AVC, however, he can minimize his losses past producing where MC equals MR 2. Here, that occurs at an output of 4,444 pounds of radishes per month. The price is $0.18 per pound, and boilerplate total price is $0.23 per pound. He loses $0.05 per pound, or $222.twenty per month.

When producing 4,444 pounds of radishes per month, Mr. Gortari faces an boilerplate total cost of $0.23 per pound. At a price of $0.18 per pound, he loses a nickel on each pound produced. Total economic losses at an output of iv,444 pounds per calendar month are thus $222.xx per calendar month (=4,444×$0.05).

No producer likes a loss (that is, negative economic turn a profit), but the loss solution shown in Figure 9.8 "Suffering Economic Losses in the Short Run" is the best Mr. Gortari tin attain. Any level of product other than the one at which marginal toll equals marginal acquirement would produce fifty-fifty greater losses.

Suppose Mr. Gortari were to shut down and produce no radishes. Ceasing production would reduce variable costs to zero, just he would still face up fixed costs of $400 per calendar month (recall that $400 was the vertical intercept of the total cost curve in Figure 9.6 "Full Acquirement, Total Price, and Economic Turn a profit"). By shutting down, Mr. Gortari would lose $400 per month. Past continuing to produce, he loses only $222.20.

Mr. Gortari is better off producing where marginal cost equals marginal acquirement because at that output price exceeds boilerplate variable cost. Average variable cost is $0.xiv per pound, so by standing to produce he covers his variable costs, with $0.04 per pound left over to apply to fixed costs. Whenever price is greater than boilerplate variable cost, the house maximizes economical turn a profit (or minimizes economical loss) by producing the output level at which marginal revenue and marginal cost curves intersect.

Shutting Downwards to Minimize Economic Loss

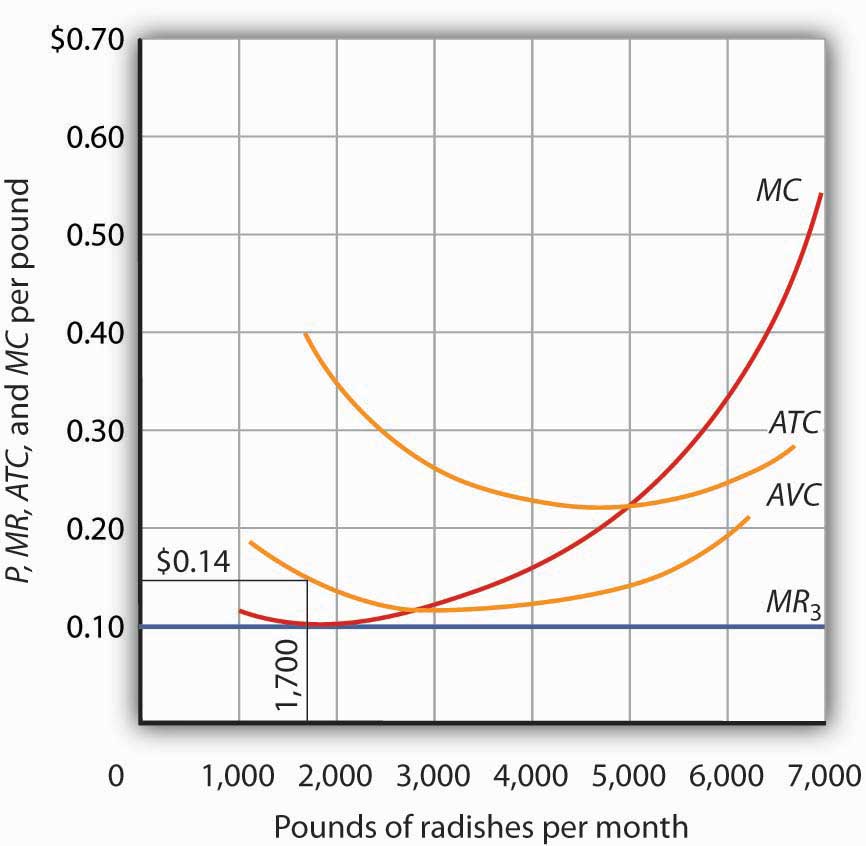

Suppose price drops beneath a firm'southward average variable cost. Now the best strategy for the firm is to shut down, reducing its output to zero. The minimum level of boilerplate variable cost, which occurs at the intersection of the marginal cost bend and the average variable cost bend, is chosen the shutdown point. Any price below the minimum value of average variable cost volition cause the business firm to shut downwardly. If the business firm were to continue producing, not only would information technology lose its fixed costs, but it would also confront an additional loss past non covering its variable costs.

Effigy ix.9 "Shutting Down" shows a case where the price of radishes drops to $0.10 per pound. Price is less than average variable cost, so Mr. Gortari not simply would lose his fixed cost only would also incur boosted losses by producing. Suppose, for example, he decided to operate where marginal cost equals marginal revenue, producing 1,700 pounds of radishes per month. Boilerplate variable cost equals $0.14 per pound, so he would lose $0.04 on each pound he produces ($68) plus his fixed cost of $400 per month. He would lose $468 per month. If he shut down, he would lose only his stock-still price. Because the price of $0.x falls below his average variable cost, his all-time grade would be to shut down.

Figure nine.ix Shutting Down

The marketplace cost of radishes drops to $0.10 per pound, so MR 3 is beneath Mr. Gortari's AVC. Thus he would suffer a greater loss by continuing to operate than past shutting down. Whenever price falls below average variable toll, the firm will shut down, reducing its production to zero.

Shutting down is not the same thing as going out of business organization. A business firm shuts down by endmost its doors; it tin reopen them whenever information technology expects to cover its variable costs. We can even recall of a house'south determination to close at the stop of the day as a kind of shutdown point; the firm makes this choice because it does non conceptualize that it will be able to cover its variable cost overnight. It expects to cover those costs the adjacent morning when information technology reopens its doors.

Marginal Cost and Supply

In the model of perfect competition, we assume that a firm determines its output by finding the bespeak where the marginal revenue and marginal toll curves intersect. Provided that price exceeds average variable cost, the house produces the quantity determined by the intersection of the two curves.

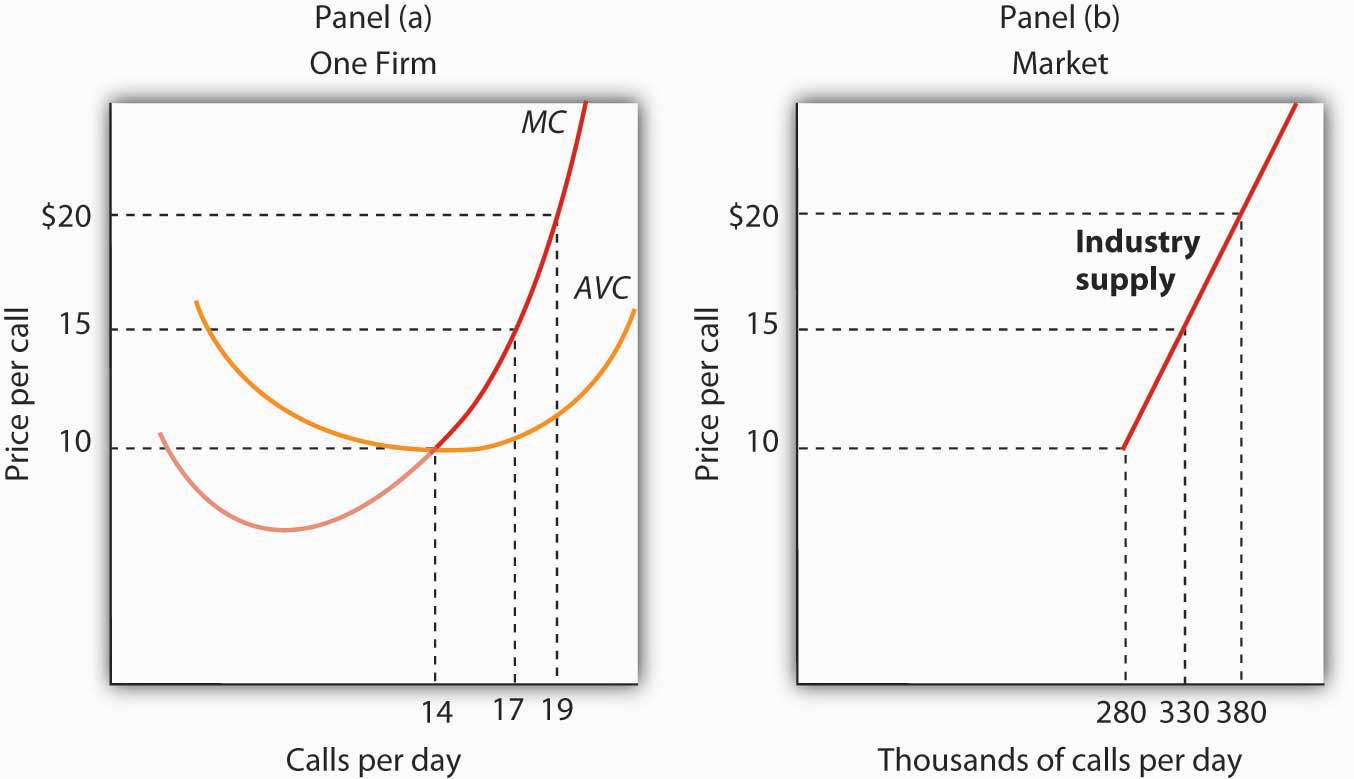

A supply bend tells us the quantity that will be produced at each price, and that is what the firm'due south marginal cost curve tells us. The firm's supply curve in the short run is its marginal cost curve for prices above the boilerplate variable cost. At prices beneath boilerplate variable toll, the house'south output drops to null.

Console (a) of Figure 9.10 "Marginal Cost and Supply" shows the boilerplate variable toll and marginal cost curves for a hypothetical astrologer, Madame LaFarge, who is in the concern of providing astrological consultations over the phone. We shall assume that this industry is perfectly competitive. At any price below $10 per call, Madame LaFarge would shut downwardly. If the cost is $x or greater, however, she produces an output at which cost equals marginal cost. The marginal price curve is thus her supply curve at all prices greater than $10.

Figure 9.10 Marginal Cost and Supply

The supply bend for a firm is that portion of its MC curve that lies in a higher place the AVC curve, shown in Console (a). To obtain the brusque-run supply bend for the industry, we add the outputs of each firm at each price. The industry supply curve is given in Panel (b).

At present suppose that the astrological forecast manufacture consists of Madame LaFarge and thousands of other firms similar to hers. The market supply curve is institute by calculation the outputs of each firm at each toll, every bit shown in Panel (b) of Effigy 9.10 "Marginal Cost and Supply". At a price of $ten per call, for example, Madame LaFarge supplies fourteen calls per day. Adding the quantities supplied by all the other firms in the market place, suppose we go a quantity supplied of 280,000. Notice that the market supply curve we have drawn is linear; throughout the volume we have made the assumption that market demand and supply curves are linear in lodge to simplify our analysis.

Looking at Effigy 9.10 "Marginal Cost and Supply", nosotros see that turn a profit-maximizing choices by firms in a perfectly competitive market volition generate a market supply curve that reflects marginal cost. Provided there are no external benefits or costs in producing a good or service, a perfectly competitive market satisfies the efficiency status.

Cardinal Takeaways

- Cost in a perfectly competitive industry is determined by the interaction of need and supply.

- In a perfectly competitive industry, a house's total revenue curve is a straight, upward-sloping line whose gradient is the market place price. Economical profit is maximized at the output level at which the slopes of the total revenue and full cost curves are equal, provided that the business firm is covering its variable cost.

- To employ the marginal decision rule in profit maximization, the firm produces the output at which marginal toll equals marginal acquirement. Economic profit per unit is price minus average total cost; total economical profit equals economic turn a profit per unit times quantity.

- If toll falls below average total cost, merely remains above boilerplate variable cost, the firm volition continue to operate in the short run, producing the quantity where MR = MC doing so minimizes its losses.

- If cost falls below average variable toll, the business firm will close down in the short run, reducing output to cypher. The lowest bespeak on the boilerplate variable price curve is called the shutdown signal.

- The firm'south supply bend in the short run is its marginal cost bend for prices greater than the minimum average variable cost.

Attempt It!

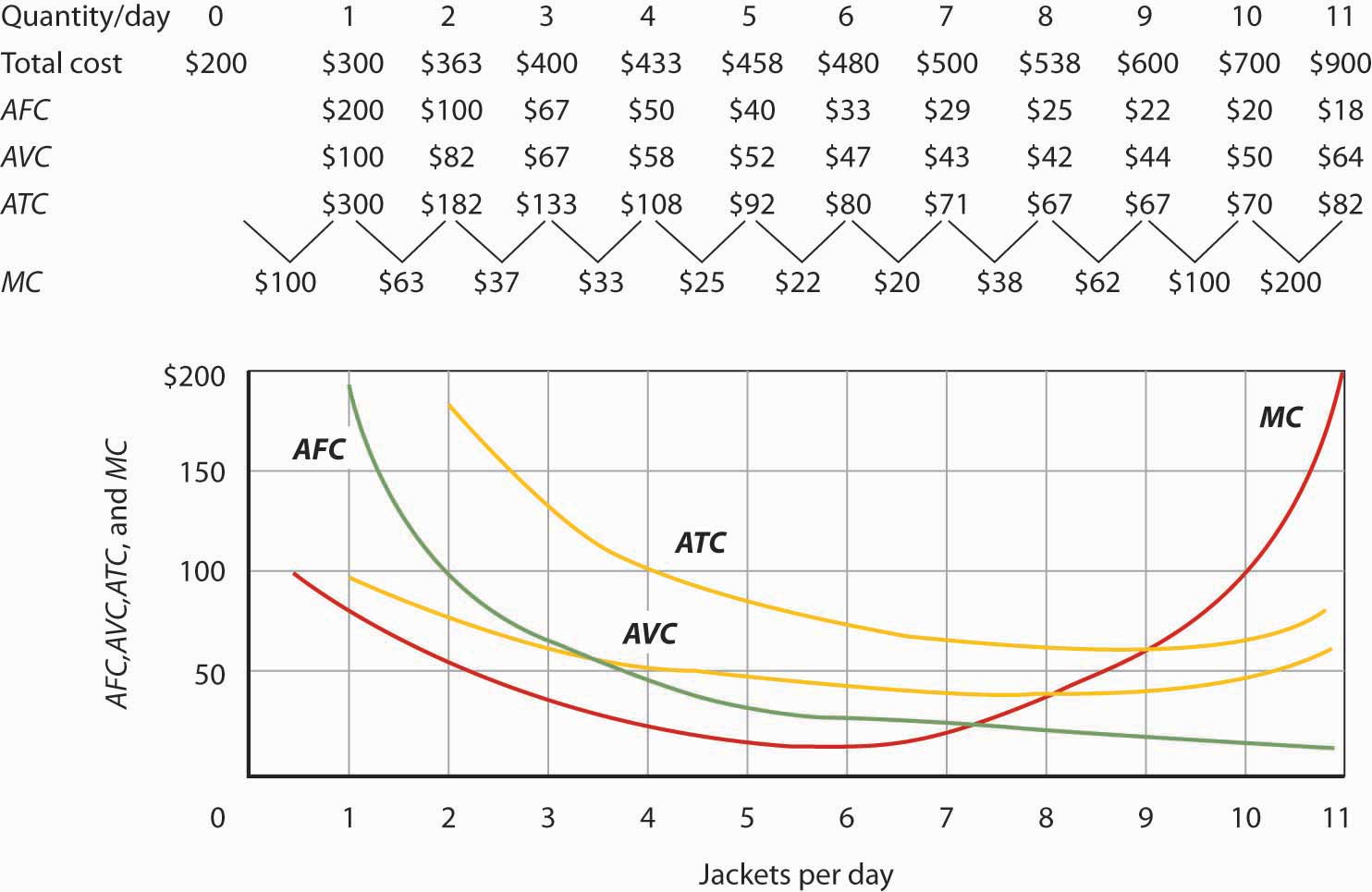

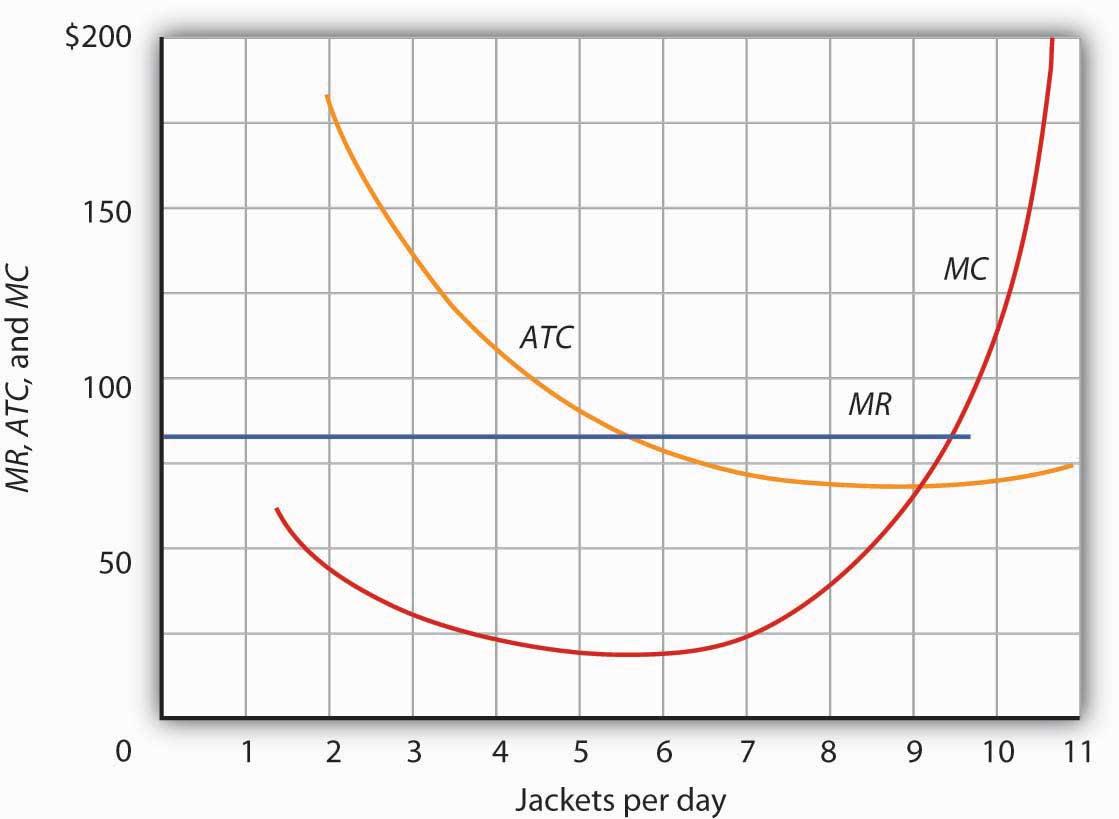

Assume that Peak Clothing, the house introduced in the chapter on production and cost, produces jackets in a perfectly competitive marketplace. Suppose the demand and supply curves for jackets intersect at a cost of $81. At present, using the marginal cost and average total toll curves for Acme shown here:

Figure 9.11

Estimate Acme'due south profit-maximizing output per day (assume the firm selects a whole number). What are Acme's economic profits per 24-hour interval?

Case in Point: Not Out of Business 'Til They Fall from the Sky

Effigy 9.12

The 66 satellites were poised to start falling from the sky. The hope was that the pieces would burn to bits on their way down through the atmosphere, but there was the chance that a building or a person would take a direct hit.

The satellites were the primary communication devices of Iridium'southward satellite phone system. Begun in 1998 equally the starting time truly global satellite system for mobile phones—providing communications across deserts, in the middle of oceans, and at the poles—Iridium expected 5 meg subscribers to pay $seven a infinitesimal to talk on $3,000 handsets. In the climate of the late 1990s, users opted for cheaper, though less secure and less comprehensive, jail cell phones. By the end of the decade, Iridium had declared bankruptcy, shut downwards operations, and was just waiting for the satellites to beginning plunging from their orbits around 2007.

The only offering for Iridium's $v billion system came from an ex-CEO of a nuclear reactor business, Dan Colussy, and information technology was for a measly $25 million. "It'south similar picking up a $150,000 Porsche 911 for $750," wrote USA Today reporter, Kevin Maney.

The purchase turned into a bonanza. In the wake of September 11, 2001, so the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq, demand for secure communications in remote locations skyrocketed. New customers included the U.S. and British militaries, as well as reporters in Iraq, who, when traveling with the military machine have been barred from using less secure systems that are easier to track. The nonprofit organization Operation Call Abode has bought fourth dimension to let members of the 81st Armor Brigade of the Washington National Guard to communicate with their families at habitation. Airlines and shipping lines have also signed up.

Every bit the new Iridium became unburdened from the debt of the old one and technology improved, the lower fixed and variable costs have contributed to Iridium's revival, but clearly a critical element in the turnaround has been increased need. The launching of an additional vii spare satellites and other tinkering have extended the life of the system to at least 2014. The firm was temporarily close down just, with its new owners and new demand for its services, has come roaring back.

Why did Colussy buy Iridium? A top executive in the new firm said that Colussy simply found the elimination of the satellites a terrible waste. Maybe he had some niche uses in listen, as even before September 11, 2001, he had begun to enroll some new customers, such as the Colombian national police, who no dubiety found the organisation useful in the fighting drug lords. But it was in the aftermath of 9/11 that its subscriber list actually began to grow and its re-opening was deemed a stroke of genius. Today Iridium's customers include ships at sea (which business relationship for about one-half of its business), airlines, military uses, and a multifariousness of commercial and humanitarian applications.

Sources: Kevin Maney, "Recall Those 'Iridium'southward Going to Fail' Jokes? Prepare to Eat Your Hat," USA Today, April 9, 2003: p. 3B. Michael Mecham, "Handheld Improvement: A Resurrected Iridium Counts Aviation, Antiterrorism Amid Its Growth Fields," Aviation Week and Space Engineering science, 161: 9 (September half dozen, 2004): p. 58. Iridium's webpage can be plant at Iridium.com.

Answer to Try It! Problem

At a price of $81, Acme's marginal revenue curve is a horizontal line at $81. The business firm produces the output at which marginal toll equals marginal acquirement; the curves intersect at a quantity of nine jackets per day. Summit'due south boilerplate total cost at this level of output equals $67, for an economic profit per jacket of $14. Meridian's economic profit per day equals about $126.

Figure 9.13

In The Long Run, What Determines The Level Of Total Production Of Goods And Services In An Economy?,

Source: https://open.lib.umn.edu/principleseconomics/chapter/9-2-output-determination-in-the-short-run/

Posted by: trainorwimen1956.blogspot.com

0 Response to "In The Long Run, What Determines The Level Of Total Production Of Goods And Services In An Economy?"

Post a Comment