Who Qualified For Mental Health Services In 1800s

History of Mental Affliction

ByHood Higher

This module is divided into three parts. The first is a cursory introduction to various criteria we employ to define or distinguish betwixt normality and abnormality. The second, largest part is a history of mental illness from the Stone Historic period to the 20th century, with a special emphasis on the recurrence of three causal explanations for mental illness; supernatural, somatogenic, and psychogenic factors. This part briefly touches upon trephination, the Greek theory of hysteria inside the context of the iv bodily humors, witch hunts, asylums, moral treatment, mesmerism, catharsis, the mental hygiene movement, deinstitutionalization, customs mental health services, and managed care. The tertiary function concludes with a brief description of the issue of diagnosis.

Learning Objectives

- Identify what the criteria used to distinguish normality from aberration are.

- Understand the difference amid the 3 main etiological theories of mental illness.

- Describe specific beliefs or events in history that exemplify each of these etiological theories (e.g., hysteria, humorism, witch hunts, asylums, moral treatments).

- Explain the differences in treatment facilities for the mentally ill (e.g., mental hospitals, asylums, customs mental health centers).

- Describe the features of the "moral treatment" arroyo used by Chiarughi, Pinel, and Tuke.

- Depict the reform efforts of Dix and Beers and the outcomes of their piece of work.

- Depict Kräpelin's nomenclature of mental affliction and the current DSM system.

History of Mental Illness

References to mental illness tin can be found throughout history. The evolution of mental illness, however, has not been linear or progressive but rather cyclical. Whether a behavior is considered normal or abnormal depends on the context surrounding the behavior and thus changes as a function of a particular time and culture. In the past, uncommon behavior or behavior that deviated from the sociocultural norms and expectations of a specific culture and period has been used as a manner to silence or control certain individuals or groups. Every bit a result, a less cultural relativist view of aberrant beliefs has focused instead on whether behavior poses a threat to oneself or others or causes so much pain and suffering that it interferes with 1's work responsibilities or with i'south relationships with family unit and friends.

Throughout history there take been three full general theories of the etiology of mental illness: supernatural, somatogenic, and psychogenic. Supernatural theories aspect mental disease to possession by evil or demonic spirits, displeasure of gods, eclipses, planetary gravitation, curses, and sin. Somatogenic theories identify disturbances in physical operation resulting from either illness, genetic inheritance, or brain damage or imbalance. Psychogenic theories focus on traumatic or stressful experiences, maladaptive learned associations and cognitions, or distorted perceptions. Etiological theories of mental illness decide the care and treatment mentally sick individuals receive. Equally we will see below, an individual believed to exist possessed by the devil volition be viewed and treated differently from an individual believed to exist suffering from an backlog of yellow bile. Their treatments will also differ, from exorcism to blood-letting. The theories, yet, remain the aforementioned. They coexist besides as recycle over time.

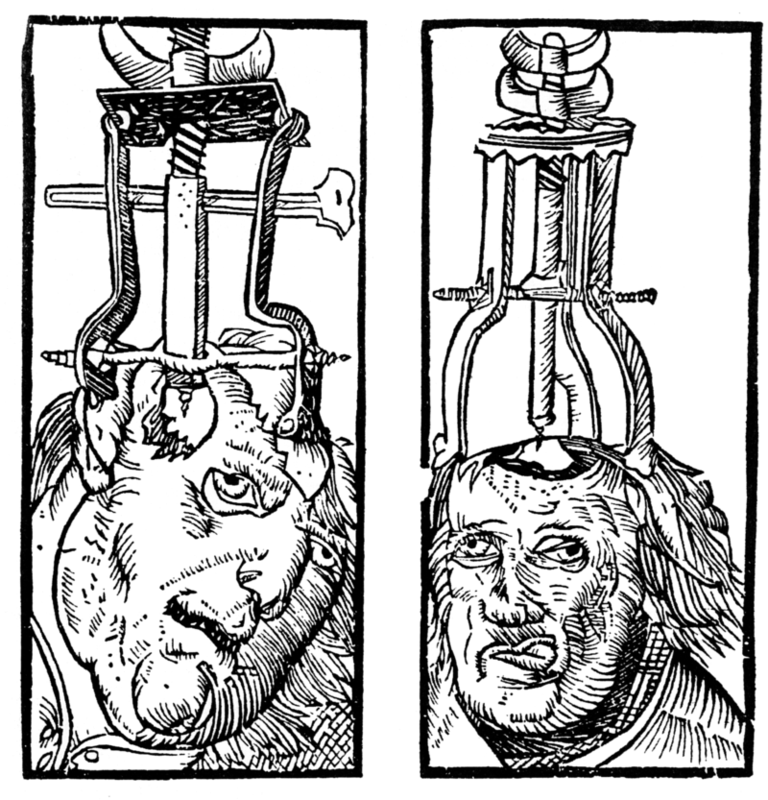

Trephination is an example of the earliest supernatural caption for mental illness. Examination of prehistoric skulls and cave fine art from as early equally 6500 BC has identified surgical drilling of holes in skulls to treat head injuries and epilepsy as well every bit to allow evil spirits trapped within the skull to exist released (Restak, 2000). Around 2700 BC, Chinese medicine's concept of complementary positive and negative bodily forces ("yin and yang") attributed mental (and concrete) illness to an imbalance between these forces. As such, a harmonious life that immune for the proper balance of yin and yang and movement of vital air was essential (Tseng, 1973).

Mesopotamian and Egyptian papyri from 1900 BC describe women suffering from mental disease resulting from a wandering uterus (later named hysteria by the Greeks): The uterus could become dislodged and attached to parts of the torso like the liver or breast cavity, preventing their proper functioning or producing varied and sometimes painful symptoms. As a upshot, the Egyptians, and later the Greeks, as well employed a somatogenic handling of strong smelling substances to guide the uterus dorsum to its proper location (pleasant odors to lure and unpleasant ones to dispel).

Throughout classical antiquity nosotros meet a return to supernatural theories of demonic possession or godly displeasure to account for aberrant behavior that was across the person's command. Temple omnipresence with religious healing ceremonies and incantations to the gods were employed to help in the healing process. Hebrews saw madness equally punishment from God, so treatment consisted of confessing sins and repenting. Physicians were too believed to be able to comfort and cure madness, however.

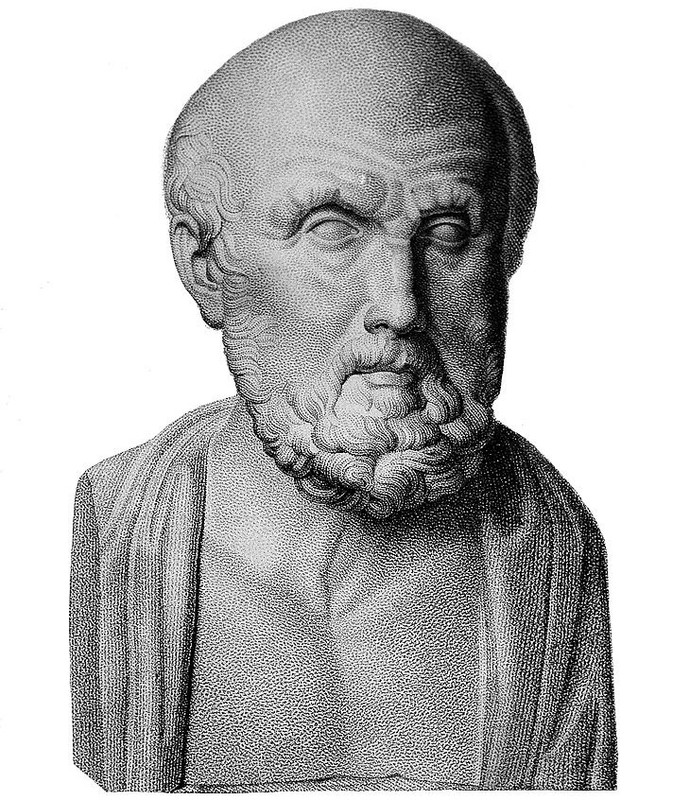

Greek physicians rejected supernatural explanations of mental disorders. It was around 400 BC that Hippocrates (460–370 BC) attempted to separate superstition and religion from medicine by systematizing the belief that a deficiency in or specially an excess of ane of the 4 essential actual fluids (i.e., humors)—blood, yellow bile, black bile, and phlegm—was responsible for physical and mental illness. For instance, someone who was as well temperamental suffered from too much claret and thus blood-letting would be the necessary handling. Hippocrates classified mental affliction into one of iv categories—epilepsy, mania, melancholia, and brain fever—and like other prominent physicians and philosophers of his time, he did not believe mental disease was shameful or that mentally ill individuals should be held accountable for their behavior. Mentally sick individuals were cared for at home by family members and the land shared no responsibility for their care. Humorism remained a recurrent somatogenic theory up until the 19th century.

While Greek dr. Galen (AD 130–201) rejected the notion of a uterus having an animistic soul, he agreed with the notion that an imbalance of the iv bodily fluids could cause mental affliction. He also opened the door for psychogenic explanations for mental illness, however, by allowing for the experience of psychological stress as a potential cause of abnormality. Galen's psychogenic theories were ignored for centuries, nevertheless, as physicians attributed mental illness to physical causes throughout most of the millennium.

By the late Middle Ages, economic and political turmoil threatened the power of the Roman Catholic church. Betwixt the 11th and 15th centuries, supernatural theories of mental disorders over again dominated Europe, fueled by natural disasters like plagues and famines that lay people interpreted as brought well-nigh by the devil. Superstition, astrology, and abracadabra took hold, and common treatments included prayer rites, relic touching, confessions, and atonement. First in the 13th century the mentally sick, particularly women, began to be persecuted equally witches who were possessed. At the superlative of the witch hunts during the 15th through 17th centuries, with the Protestant Reformation having plunged Europe into religious strife, ii Dominican monks wrote the Malleus Maleficarum (1486) as the ultimate manual to guide witch hunts. Johann Weyer and Reginald Scot tried to convince people in the mid- to late-16th century that defendant witches were actually women with mental illnesses and that mental illness was not due to demonic possession but to faulty metabolism and affliction, just the Church building's Inquisition banned both of their writings. Witch-hunting did non decline until the 17th and 18th centuries, later more 100,000 presumed witches had been burned at the pale (Schoeneman, 1977; Zilboorg & Henry, 1941).

Modern treatments of mental illness are most associated with the establishment of hospitals and asylums beginning in the 16th century. Such institutions' mission was to house and confine the mentally ill, the poor, the homeless, the unemployed, and the criminal. State of war and economic depression produced vast numbers of undesirables and these were separated from gild and sent to these institutions. Two of the most well-known institutions, St. Mary of Bethlehem in London, known as Bedlam, and the Hôpital Général of Paris—which included La Salpêtrière, La Pitié, and La Bicêtre—began housing mentally ill patients in the mid-16th and 17th centuries. Equally confinement laws focused on protecting the public from the mentally sick, governments became responsible for housing and feeding undesirables in exchange for their personal liberty. Near inmates were institutionalized against their volition, lived in filth and chained to walls, and were commonly exhibited to the public for a fee. Mental illness was nonetheless viewed somatogenically, so treatments were like to those for physical illnesses: purges, bleedings, and emetics.

While inhumane past today's standards, the view of insanity at the time likened the mentally sick to animals (i.due east., animalism) who did not have the chapters to reason, could not command themselves, were capable of violence without provocation, did not have the same physical sensitivity to pain or temperature, and could alive in miserable conditions without complaint. As such, instilling fear was believed to exist the best way to restore a disordered listen to reason.

By the 18th century, protests rose over the conditions under which the mentally ill lived, and the 18th and 19th centuries saw the growth of a more humanitarian view of mental disease. In 1785 Italian physician Vincenzo Chiarughi (1759–1820) removed the chains of patients at his St. Boniface hospital in Florence, Italy, and encouraged good hygiene and recreational and occupational grooming. More well known, French doc Philippe Pinel (1745–1826) and former patient Jean-Baptise Pussin created a "traitement moral" at La Bicêtre and the Salpêtrière in 1793 and 1795 that likewise included unshackling patients, moving them to well-aired, well-lit rooms, and encouraging purposeful action and freedom to move about the grounds (Micale, 1985).

In England, humanitarian reforms rose from religious concerns. William Tuke (1732–1822) urged the Yorkshire Lodge of (Quaker) Friends to institute the York Retreat in 1796, where patients were guests, non prisoners, and where the standard of care depended on dignity and courtesy every bit well as the therapeutic and moral value of physical work (Bell, 1980).

While America had asylums for the mentally ill—such as the Pennsylvania Hospital in Philadelphia and the Williamsburg Hospital, established in 1756 and 1773—the somatogenic theory of mental disease of the fourth dimension—promoted especially by the male parent of America psychiatry, Benjamin Rush (1745–1813)—had led to treatments such as claret-letting, gyrators, and tranquilizer chairs. When Tuke'south York Retreat became the model for half of the new private asylums established in the United States, yet, psychogenic treatments such equally empathetic care and physical labor became the hallmarks of the new American asylums, such as the Friends Asylum in Frankford, Pennsylvania, and the Bloomingdale Aviary in New York City, established in 1817 and 1821 (Grob, 1994).

Moral handling had to be abandoned in America in the second one-half of the 19th century, withal, when these asylums became overcrowded and custodial in nature and could no longer provide the space nor attention necessary. When retired school instructor Dorothea Dix discovered the negligence that resulted from such conditions, she advocated for the establishment of state hospitals. Between 1840 and1880, she helped establish over 30 mental institutions in the United States and Canada (Viney & Zorich, 1982). By the late 19th century, moral treatment had given way to the mental hygiene movement, founded by former patient Clifford Beers with the publication of his 1908 memoir A Mind That Found Itself. Riding on Pasteur's breakthrough germ theory of the 1860s and 1870s and especially on the early on 20th century discoveries of vaccines for cholera, syphilis, and typhus, the mental hygiene movement reverted to a somatogenic theory of mental disease.

European psychiatry in the tardily 18th century and throughout the 19th century, nevertheless, struggled between somatogenic and psychogenic explanations of mental illness, particularly hysteria, which caused physical symptoms such as blindness or paralysis with no apparent physiological explanation. Franz Anton Mesmer (1734–1815), influenced by gimmicky discoveries in electricity, attributed hysterical symptoms to imbalances in a universal magnetic fluid establish in individuals, rather than to a wandering uterus (Forrest, 1999). James Complect (1795–1860) shifted this conventionalities in mesmerism to one in hypnosis, thereby proposing a psychogenic treatment for the removal of symptoms. At the time, famed Salpetriere Hospital neurologist Jean-Martin Charcot (1825–1893), and Ambroise Auguste Liébault (1823–1904) and Hyppolyte Bernheim (1840–1919) of the Nancy School in France, were engaged in a biting etiological battle over hysteria, with Charcot maintaining that the hypnotic suggestibility underlying hysteria was a neurological condition while Liébault and Bernheim believed it to be a general trait that varied in the population. Josef Breuer (1842–1925) and Sigmund Freud (1856–1939) would resolve this dispute in favor of a psychogenic caption for mental illness by treating hysteria through hypnosis, which somewhen led to the cathartic method that became the precursor for psychoanalysis during the commencement one-half of the 20th century.

Psychoanalysis was the dominant psychogenic treatment for mental illness during the outset half of the 20th century, providing the launching pad for the more than than 400 different schools of psychotherapy found today (Magnavita, 2006). Well-nigh of these schools cluster effectually broader behavioral, cerebral, cognitive-behavioral, psychodynamic, and client-centered approaches to psychotherapy applied in individual, marital, family, or grouping formats. Negligible differences take been found among all these approaches, however; their efficacy in treating mental illness is due to factors shared among all of the approaches (non particular elements specific to each arroyo): the therapist-patient alliance, the therapist's allegiance to the therapy, therapist competence, and placebo effects (Luborsky et al., 2002; Messer & Wampold, 2002).

In dissimilarity, the leading somatogenic treatment for mental illness tin be found in the establishment of the starting time psychotropic medications in the mid-20th century. Restraints, electro-convulsive shock therapy, and lobotomies continued to be employed in American state institutions until the 1970s, simply they chop-chop fabricated fashion for a burgeoning pharmaceutical industry that has viewed and treated mental affliction every bit a chemic imbalance in the brain.

Both etiological theories coexist today in what the psychological subject field holds as the biopsychosocial model of explaining man behavior. While individuals may exist built-in with a genetic predisposition for a certain psychological disorder, certain psychological stressors need to be present for them to develop the disorder. Sociocultural factors such every bit sociopolitical or economic unrest, poor living conditions, or problematic interpersonal relationships are too viewed as contributing factors. However much we want to believe that we are to a higher place the treatments described to a higher place, or that the nowadays is always the most enlightened fourth dimension, allow us not forget that our thinking today continues to reflect the same underlying somatogenic and psychogenic theories of mental illness discussed throughout this brief ix,000-twelvemonth history.

Diagnosis of Mental Affliction

Progress in the handling of mental illness necessarily implies improvements in the diagnosis of mental illness. A standardized diagnostic classification system with agreed-upon definitions of psychological disorders creates a shared language among mental-health providers and aids in clinical research. While diagnoses were recognized as far back as the Greeks, it was non until 1883 that German psychiatrist Emil Kräpelin (1856–1926) published a comprehensive system of psychological disorders that centered around a pattern of symptoms (i.e., syndrome) suggestive of an underlying physiological cause. Other clinicians as well suggested popular nomenclature systems but the need for a single, shared organisation paved the style for the American Psychiatric Association'south 1952 publication of the starting time Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM).

The DSM has undergone various revisions (in 1968, 1980, 1987, 1994, 2000, 2013), and information technology is the 1980 DSM-Iii version that began a multiaxial classification system that took into account the entire private rather than only the specific problem behavior. Axes I and 2 incorporate the clinical diagnoses, including intellectual disability and personality disorders. Axes III and IV listing any relevant medical conditions or psychosocial or environmental stressors, respectively. Axis 5 provides a global assessment of the individual's level of performance. The about recent version -- the DSM-v-- has combined the showtime three axes and removed the concluding 2. These revisions reverberate an attempt to assist clinicians streamline diagnosis and work better with other diagnostic systems such as wellness diagnoses outlined past the Earth Wellness Arrangement.

While the DSM has provided a necessary shared linguistic communication for clinicians, aided in clinical research, and allowed clinicians to exist reimbursed by insurance companies for their services, information technology is non without criticism. The DSM is based on clinical and research findings from Western culture, primarily the Usa. Information technology is also a medicalized chiselled nomenclature system that assumes disordered behavior does non differ in caste only in kind, as opposed to a dimensional classification system that would plot matted behavior along a continuum. Finally, the number of diagnosable disorders has tripled since it was first published in 1952, and so that almost half of Americans will have a diagnosable disorder in their lifetime, contributing to the continued concern of labeling and stigmatizing mentally ill individuals. These concerns appear to exist relevant even in the DSM-5 version that came out in May of 2013.

Outside Resources

- Video: An introduction to and overview of psychology, from its origins in the nineteenth century to current study of the brain\'due south biochemistry.

- http://world wide web.learner.org/series/discoveringpsychology/01/e01expand.html

- Video: The BBC provides an overview of ancient Greek approaches to health and medicine.

- https://world wide web.tes.com/teaching-resources/aboriginal-greek-approaches-to-wellness-and-medicine-6176019

- Web: Images from the History of Medicine. Search \\\"mental illness\\\"

- http://ihm.nlm.nih.gov/luna/servlet/view/all

- Web: Science Museum Brought to Life

- http://world wide web.sciencemuseum.org.united kingdom of great britain and northern ireland/broughttolife/themes/menalhealthandillness.aspx

- Web: The Social Psychology Network provides a number of links and resources.

- https://www.socialpsychology.org/history.htm

- Web: The Wellcome Library. Search \\\"mental illness\\\".

- http://wellcomelibrary.org/

- Web: UCL Department of Science and Technology Studies

- https://world wide web.ucl.ac.great britain/sts/

- Web: United states of america National Library of Medicine

- http://vsearch.nlm.nih.gov/vivisimo/cgi-bin/query-meta?query=mental+illness&v:project=nlm-main-website

Discussion Questions

- What does it hateful to say that someone is mentally ill? What criteria are commonly considered to decide whether someone is mentally ill?

- Describe the difference between supernatural, somatogenic, and psychogenic theories of mental illness and how subscribing to a particular etiological theory determines the type of treatment used.

- How did the Greeks describe hysteria and what treatment did they prescribe?

- Depict humorism and how it explained mental illness.

- Describe how the witch hunts came near and their relationship to mental disease.

- Draw the development of treatment facilities for the mentally insane, from asylums to community mental wellness centers.

- Describe the humane treatment of the mentally ill brought almost by Chiarughi, Pinel, and Tuke in the tardily 18th and early 19th centuries and how it differed from the care provided in the centuries preceding it.

- Depict William Tuke's handling of the mentally ill at the York Retreat inside the context of the Quaker Order of Friends. What influence did Tuke'south handling have in other parts of the world?

- What are the 20th-century treatments resulting from the psychogenic and somatogenic theories of mental disease?

- Describe why a nomenclature system is of import and how the leading classification system used in the The states works. Draw some concerns with regard to this system.

Vocabulary

- Animism

- The conventionalities that everyone and everything had a "soul" and that mental disease was due to animistic causes, for example, evil spirits controlling an individual and his/her behavior.

- Asylum

- A place of refuge or safety established to confine and care for the mentally sick; forerunners of the mental hospital or psychiatric facility.

- A model in which the interaction of biological, psychological, and sociocultural factors is seen as influencing the development of the individual.

- Cathartic method

- A therapeutic procedure introduced by Breuer and developed further by Freud in the late 19th century whereby a patient gains insight and emotional relief from recalling and reliving traumatic events.

- Cultural relativism

- The idea that cultural norms and values of a guild tin can only be understood on their ain terms or in their own context.

- Etiology

- The causal clarification of all of the factors that contribute to the development of a disorder or disease.

- Humorism (or humoralism)

- A belief held by aboriginal Greek and Roman physicians (and until the 19th century) that an excess or deficiency in any of the iv bodily fluids, or humors—claret, black bile, yellow bile, and phlegm—direct affected their health and temperament.

- Hysteria

- Term used past the ancient Greeks and Egyptians to describe a disorder believed to be caused by a adult female's uterus wandering throughout the body and interfering with other organs (today referred to as conversion disorder, in which psychological problems are expressed in physical grade).

- Maladaptive

- Term referring to behaviors that crusade people who take them concrete or emotional impairment, forbid them from operation in daily life, and/or indicate that they take lost bear on with reality and/or cannot control their thoughts and beliefs (likewise chosen dysfunctional).

- Mesmerism

- Derived from Franz Anton Mesmer in the late 18th century, an early version of hypnotism in which Mesmer claimed that hysterical symptoms could be treated through beast magnetism emanating from Mesmer'due south trunk and permeating the universe (and subsequently through magnets); later explained in terms of high suggestibility in individuals.

- Psychogenesis

- Developing from psychological origins.

- Somatogenesis

- Developing from physical/bodily origins.

- Supernatural

- Developing from origins beyond the visible observable universe.

- Syndrome

- Involving a particular grouping of signs and symptoms.

- "Traitement moral" (moral handling)

- A therapeutic regimen of improved nutrition, living conditions, and rewards for productive beliefs that has been attributed to Philippe Pinel during the French Revolution, when he released mentally ill patients from their restraints and treated them with compassion and dignity rather than with contempt and denigration.

- Trephination

- The drilling of a hole in the skull, presumably as a manner of treating psychological disorders.

References

- Bell, 50. Five. (1980). Treating the mentally ill: From colonial times to the present. New York: Praeger.

- Forrest, D. (1999). Hypnotism: A history. New York: Penguin.

- Grob, Yard. N. (1994). The mad among us: A history of the care of America's mentally sick. New York: Free Press.

- Luborsky, L., Rosenthal, R., Diguer, L., Andrusyna, T. P., Berman, J. Due south., Levitt, J. T., . . . Krause, E. D. (2002). The dodo bird verdict is alive and well—mostly. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practise, 9, 2–12.

- Messer, Due south. B., & Wampold, B. East. (2002). Let's face up facts: Common factors are more strong than specific therapy ingredients. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, ix(1), 21–25.

- Micale, 1000. S. (1985). The Salpêtrière in the age of Charcot: An institutional perspective on medical history in the belatedly nineteenth century. Journal of Contemporary History, 20, 703–731.

- Restak, R. (2000). Mysteries of the mind. Washington, DC: National Geographic Order.

- Schoeneman, T. J. (1977). The role of mental illness in the European witch hunts of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries: An cess. Journal of the History of the Behavioral Sciences, 13(four), 337–351.

- Tseng, W. (1973). The development of psychiatric concepts in traditional Chinese medicine. Athenaeum of General Psychiatry, 29, 569–575.

- Viney, W., & Zorich, S. (1982). Contributions to the history of psychology: XXIX. Dorothea Dix and the history of psychology. Psychological Reports, 50, 211–218.

- Zilboorg, G., & Henry, G. Westward. (1941). A history of medical psychology. New York: W. W. Norton.

Authors

Creative Commons License

History of Mental Illness past Ingrid G. Farreras is licensed nether a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. Permissions beyond the telescopic of this license may be available in our Licensing Agreement.

History of Mental Illness past Ingrid G. Farreras is licensed nether a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. Permissions beyond the telescopic of this license may be available in our Licensing Agreement. How to cite this Noba module using APA Style

Farreras, I. M. (2022). History of mental illness. In R. Biswas-Diener & Eastward. Diener (Eds), Noba textbook serial: Psychology. Champaign, IL: DEF publishers. Retrieved from http://noba.to/65w3s7exWho Qualified For Mental Health Services In 1800s,

Source: https://nobaproject.com/modules/history-of-mental-illness

Posted by: trainorwimen1956.blogspot.com

0 Response to "Who Qualified For Mental Health Services In 1800s"

Post a Comment